Chapter 9. A War Dance and a Prophecy

“The message came through of the salmon going through the ice waterfall. It was going to go away from the river. At the time, they’re like, what? How are the salmon going to go away?”

– Michael Preston, Winnemem Wintu

Listen and subscribe to The Spiritual Edge wherever you listen to podcasts - Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Google Podcasts.

By Judy Silber

I’m climbing up the side of a big, unusual kind of truck parked outside the Livingston Stone National Fish Hatchery, just below Shasta Dam. At the top, wearing black galoshes, is Beau Hopkins of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

BEAU HOPKINS: Yeah, I’m standing in approximately three-foot of water right now and I am surrounded by fish, all kinds of males and female salmon— winter-run salmon and spring-run Chinook salmon

He’s a fish culturist, someone who breeds fish.

HOPKINS: And we are going through them right now and tagging them. And taking a genetic punch out of them.

The tagging and punching is to help one species of Chinook salmon, the winter-run, an endangered species. In the 1990s, alarmed by the low numbers of returning winter-run Chinook, the federal government built this conservation hatchery. They named it after Livingston Stone, a 19th-century fish culturist who famously set up this area’s first hatchery.

Beau Hopkins reaches down and grabs a small-ish fish from the lot. He holds it up for me to see.

Like the others, this fish was caught in traps about eight miles downriver, at a dam that went up shortly after Shasta. It’s now the furthest point migrating salmon can swim. They would keep going but they can’t so they’re forced to spawn on the hot, Sacramento valley floor in less-than-ideal conditions. From the traps, the fish are loaded onto this truck that brings them to here.

HOPKINS: So this is a nice, male winter-run Chinook salmon.

The government would like to use a winter-run fish like this to help reintroduce salmon into the McCloud River. The McCloud is one of the main tributaries of Shasta Dam and the fish have not swum there since the 1940s – when the dam was built.

JUDY SILBER: How can you tell it’s a male?

HOPKINS: I’m looking at the hook jaw. And It’s a little slender and it’s dark in color. It has a lot of good, male features to it.

He punches a hole in one of its fins.

HOPKINS: About the size of a hole punch

The sample will be sent up to a genetics lab in Washington State.

HOPKINS: And they will be able to tell us if it is winter-run or not.

It will also look at other genetic markers to help hatchery employees pick the most diverse group of salmon to breed. Any winter-run not used for breeding will be trucked back, near to where they were found.

HOPKINS: And they can spawn naturally in the river there. In the Sacramento River.

Spring-run fish are also migrating upriver at this time of year. And like the winter-run, they’re trying to get above the dams. So they, too, get caught in the traps.

HOPKINS: So this is an example of a fish that’s probably going to be a spring run. It’s a lot more silvery. It’s got a more life left in it.

Beau Hopkins holds the fish in his hands, and I look this large, silvery creature in the eye. And something happens inside of me. It’s like I sense its weariness, how far it’s traveled. Thousands of miles from spawning grounds to the ocean, up and down the coast, and then returning up the river again. The Winnemem Wintu have told me that Chinook salmon are a magical fish. And now I get it. It is a living, sentient creature. Its determination is palpable. Right now, it’s a fish out of water, unable to reach its final destination. Its destiny has become part of the legacy of Shasta Dam. The Winnemem Wintu want to change that.

SILBER: I’m here with Lyla June Johnston, again.

SILBER: So Lyla, you wrote a song called Time Traveler, that was in part influenced by the Winnemem Wintu.

LYLA JUNE: Yeah, I called it Time Traveler because in a way, even though our bodies don’t make it into the future because we die, our actions do ripple out through time. And so, I really wanted to articulate, like what does it mean to be a good ancestor. And to think forward into the future. And there’s a place in the Winnemem Wintu McCloud River Basin where one of their ancestors planted these fruit trees, and that actually is mentioned in my song, because the Winnemem Wintu, along with many other elders across the nation, whom I’ve been lucky to learn from, they inspired that line, to plant trees whose fruit you’ll never taste, for people you’ll never meet.

The Winnemem Wintu are busy planting seeds for the future, including efforts to return salmon to the McCloud River, the heart of their homelands. They’ve never given up hope they could get them back.

The government is focused on saving just the winter-run. The Winnemem Wintu want all salmon runs back in their river. But for a long time, they didn’t know how to deal with the challenge of Shasta Dam.

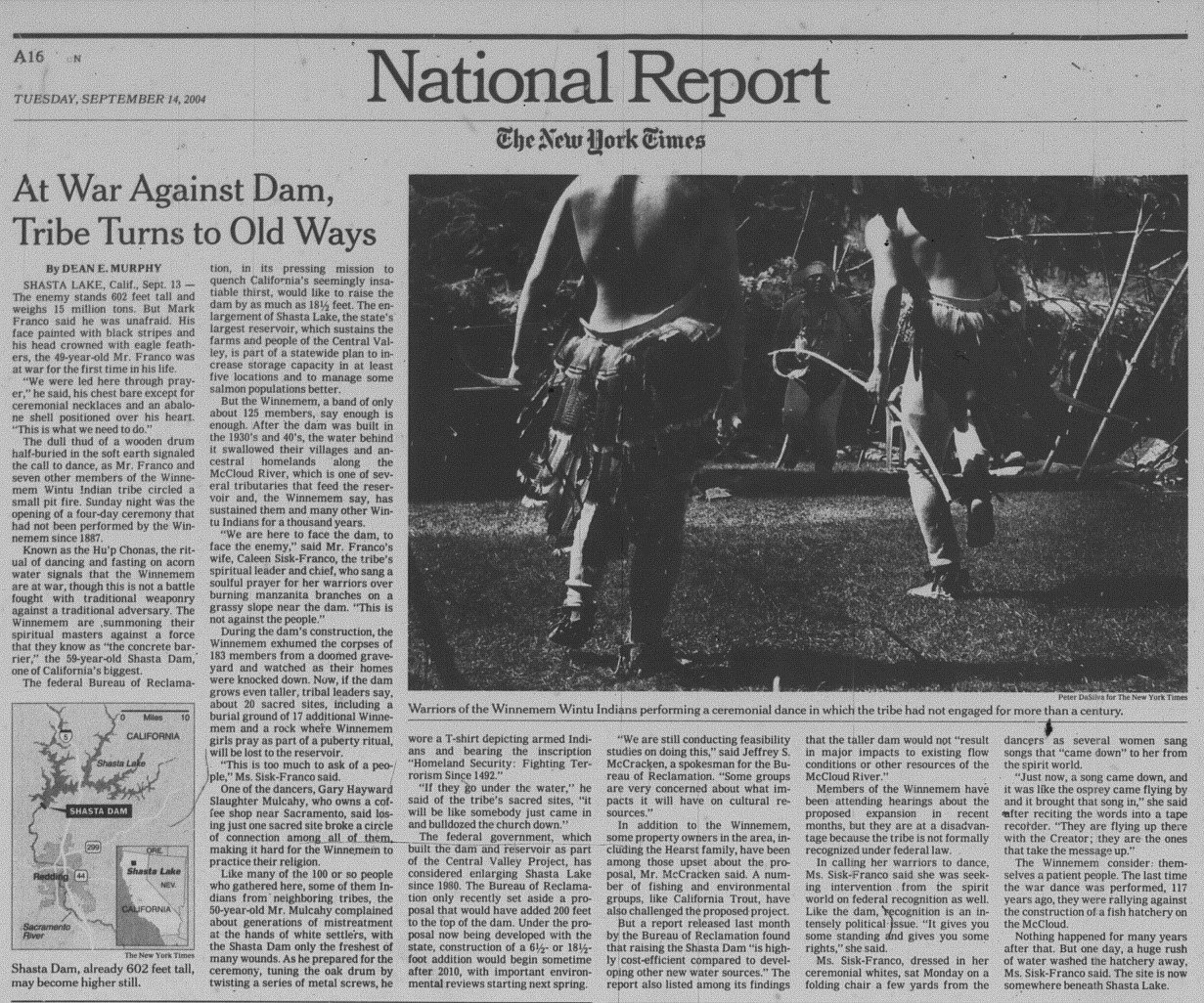

That began to change in 2004. The U.S. Bureau of Reclamation was ramping up plans for the Shasta Dam and Reservoir Enlargement Project. This was a real low point for Winnemem Wintu morale. The dam’s original construction had caused so much damage. And now, a bigger dam threatened more of their sacred sites. Sites the Winnemem Wintu considered critical to continue their culture. The idea of a higher dam disturbed them a lot.

CHIEF CALEEN SISK: Because they were trying to slide it in, And we’re going through this the second time. They’ve already burdened us one time with flooding all of our places and us, coming up with nothing..

When the original dam was built back in the 1940s, no one asked the Winnemem Wintu what they thought. This time around, they had a chance to give input. Before submitting official responses, they went up into the mountains to pray.

CHIEF SISK: We’re trying to file all these papers, take those papers to the mountains, we’d pray over those papers before we’d submit them. And we were told that we needed to tell the world.

CHIEF SISK: You’re going to do this war dance and it’s going to help you.

They were to do a war dance.

CHIEF SISK: And so, then it was like, well where are we going to do this? And that’s what they said, you got to do it at the weapon of mass destruction. That’s the dam.

Shasta Dam.

CHIEF SISK: For us, that’s the weapon of mass destruction.

She tells me this is a prayer that came down from the mountains.

SILBER: Oh, I was going to say, when you say that prayers come down from the mountain, what mountains are we talking about?

CHIEF SISK: Like a council of the mountains came together and decided, this is what we could do. Because who are we? We have no money. We have no power. We have no champions in Congress. No one even listens to us. So we follow the council of the mountains.

Chief Caleen’s son Michael Preston says they were being called to a spiritual fight.

MICHAEL PRESTON: They call it a war dance, but it’s not really talking about war.

Over the years, Michael and I have had several big conversations about the spiritual and its place in the Winnemem Wintu worldview. He says the war dance is part of a larger fight.

PRESTON: It’s basically just not giving up on our sacred sites and our animals and the spirits and showing them that we’re not going to give up. And opposing anything that is threatening our way of life and threatening our homelands and the Shasta Dam is one of them. And has been one of them.

The problem was in 2004, none of the Winnemem Wintu knew what their war dance looked like. The last one took place before any of them were born.

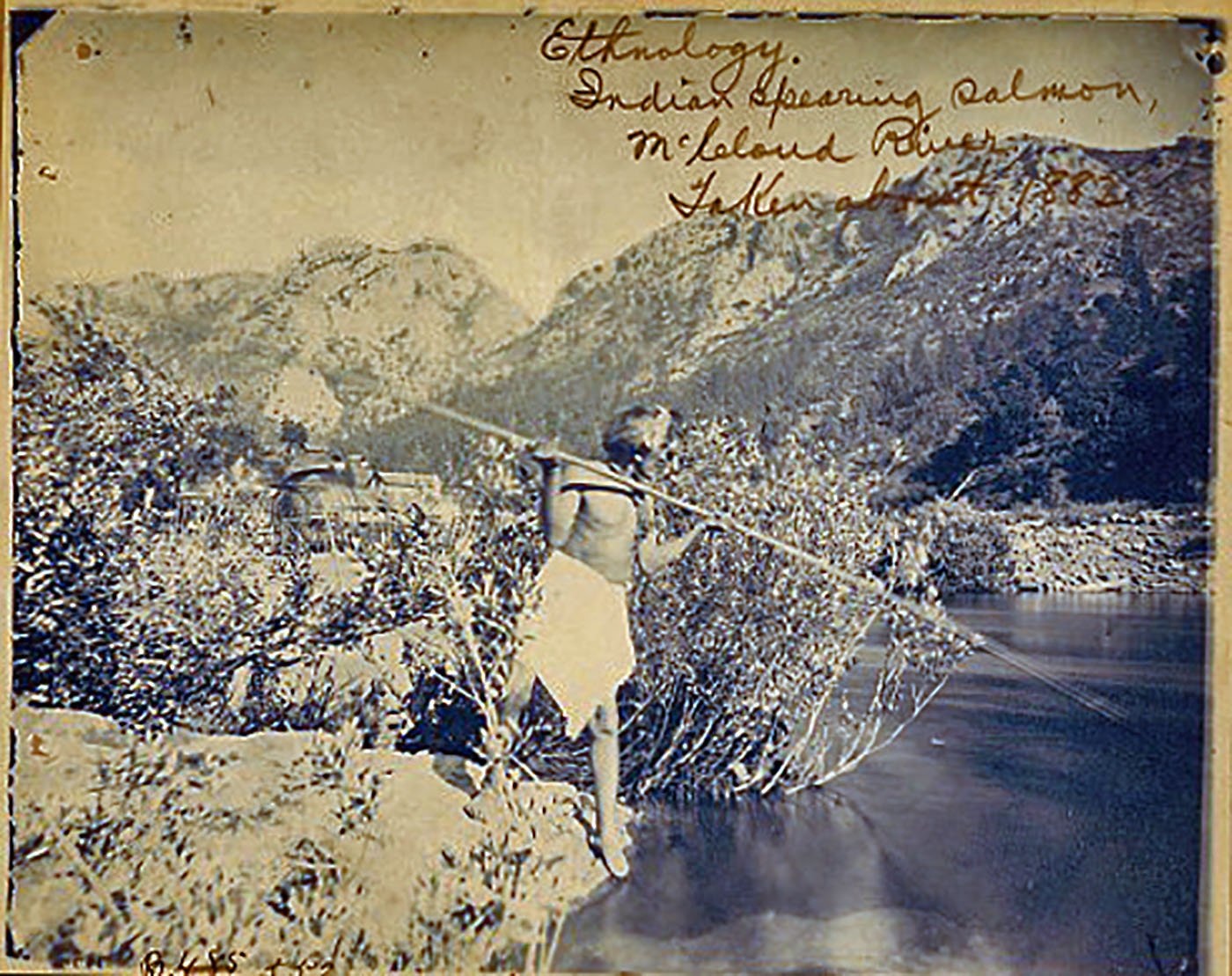

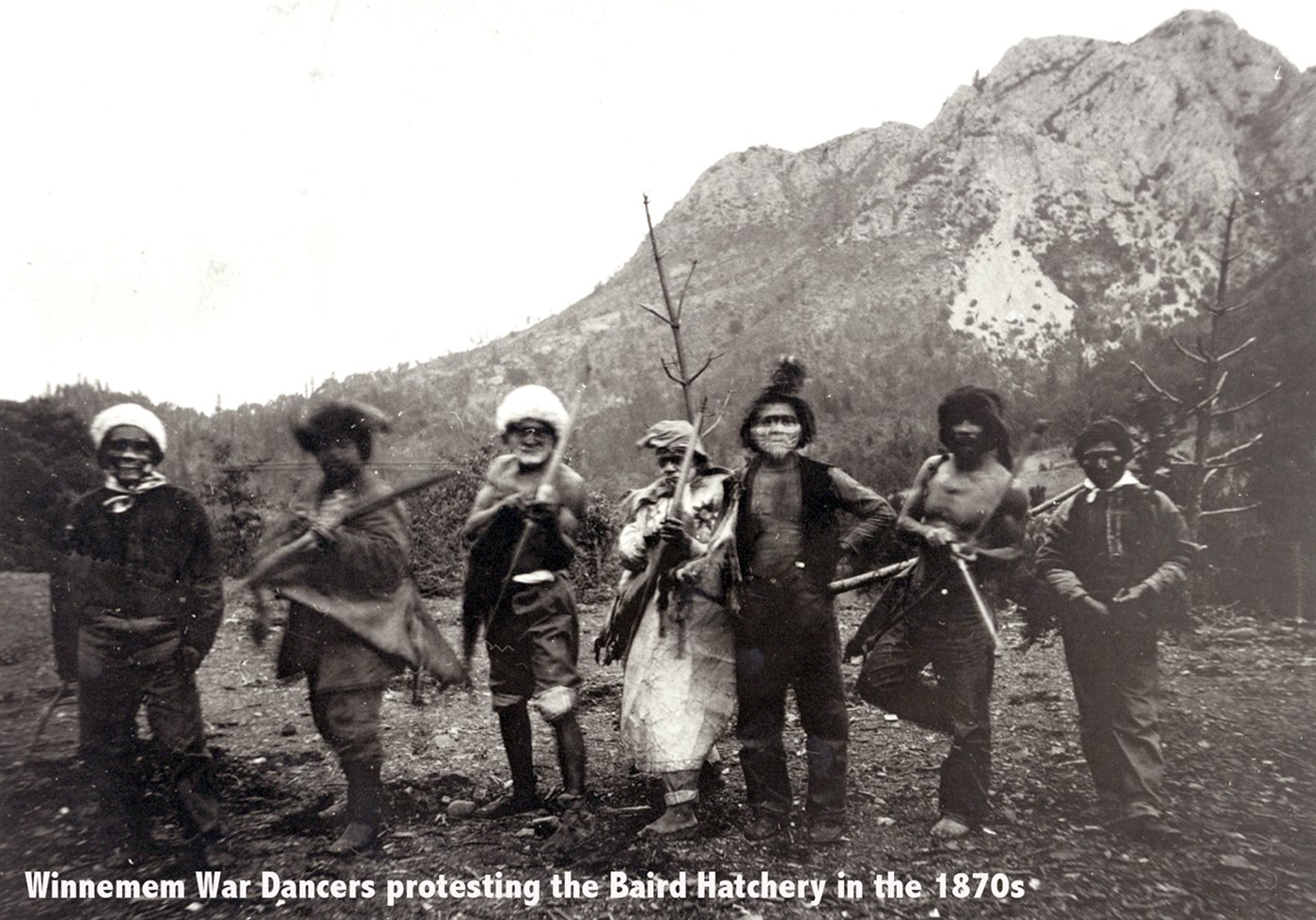

A fish expert by the name of Livingston Stone arrived to California in 1872. On orders of the U.S. Fish Commission, he set up the West Coast’s first salmon hatchery, built on their river, the McCloud.The Winnemem Wintu didn’t like the idea of a white man messing with their fish.

In his writings, Livingston Stone described a demonstration that took place on the banks of the McCloud:

ACTOR FOR LIVINGSTON STONE: They assembled in force, with their bows and arrows, on the opposite bank of the river, and spent the whole day in resentful demonstrations, or, as Mr. Woodbury expressed it, in trying to drive us off. Had they thought they could succeed in driving us off with impunity to themselves, they undoubtedly would have done so, and have hesitated at nothing to accomplish their object; but the terrible punishments which they have suffered from the hands of the whites for past misdeeds are too vivid in their memories to allow them to attempt any open or punishable violence. So, at night, they went off, and seemed subsequently to accept in general the situation.

The Winnemem Wintu risked their lives to dance. During that time, white settlers often showed no mercy toward Native people.

PRESTON: they would kill Indians right on sight at that time. No problem. They killed them like dogs. They killed them like squirrels. They killed them like whatever. Like nothing. And at the risk of that, they still did the dance because that’s what they’re supposed to do. That’s what the spirits told them to do

PRESTON: Because they were messing around with the salmon, manipulating their life, changing their natural instinct of what salmon are. That’s against the laws of creation. What are you guys doing? You’re breaking the spiritual law. And our responsibility is to stop you.

The war dance showed the Winnemem Wintu’s fierceness and commitment. It also gave rise to a prophecy that wouldn’t make sense until much later.

PRESTON: The message came through of the salmon going through the ice waterfall. It was going to go away from the river. At the time, they’re like, what? How are the salmon going to go away?

At that point, salmon were incredibly plentiful. In his reports to the government, Livingston Stone wrote with wonder about their abundance.

ACTOR FOR LIVINGSTON STONE: I have never seen anything like it anywhere, not even on the tributaries of the Columbia. On the afternoon of the 15th of August there was a space in the river... where, if a person could have balanced himself, he could actually have walked anywhere on the backs of the salmon.

They were so thick in the river in July that we counted a hundred salmon jumping out of the water in the space of a minute, making 6,000 to be actually seen in the air in an hour.

The Winnemem Wintu didn’t approve of the hatchery, but they worked there. It offered a measure of protection from settlers who were quickly encroaching on their traditional territory. The Winnemem Wintu helped catch salmon to harvest and fertilize their eggs. Livingston Stone described their skill.

ACTOR FOR LIVINGSTON STONE: The Indian swimmers, their dark heads just showing above the white foam, screaming and shouting in the icy waters and brandishing their long poles, came down the rapids at great speed, disappearing entirely now and then as they dove down into a deep hole.

The McCloud River hatchery that Livingston Stone set up sent salmon eggs all around the world. To the East Coast. To Hawaii. To Canada. To Europe. To Australia. And to New Zealand. Then in 1935, the hatchery closed down for good. Shasta Dam went up. It displaced the Winnemem Wintu from the McCloud River. and blocked salmon from swimming upstream.

Half a century later, Caleen Sisk became chief of the Winnemem Wintu. She took over leadership from her great aunt, Florence Jones, who died in 2003. A short time later, plans to build Shasta Dam higher began ramping up. The Winnemem Wintu confronted the idea of loss all over again.

Not too long after, the Winnemem Wintu received that message to revive the war dance. It hadn’t been done in more than 100 years.

CHIEF SISK: We didn't even have songs for a war dance. Right? And I’m thinking, okay, if we’re going to do this war dance, I just have to believe we’re going to do this war dance. And that it will come together and we’ll know what we’re doing.

Community members started to have dreams and visions.

CHIEF SISK: So, every person, whatever age they are, they might come up and say, hey, I had this dream about this. Or I saw it like this. Or what color it was. It’s a shared event that we’re getting ready for and everyone who’s getting ready could be a vessel for information, you know.

In addition to figuring out regalia, dances, songs, they needed a permit from the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation.

CHIEF SISK: And so we said, ‘This is what we need to do. We need to do that right over here on the dam.’ And this is after 9/11 and so our dates, because we do things in fours…So four days, which included 9/11. And they said, ‘Oh no. You can’t be dancing 9/11.’ It’s like okay, we’ll move it.

The Winnemem Wintu agreed to change the date to avoid the anniversary of the 9/11 New York Twin Tower attacks. But the haggling didn’t stop there.

CHIEF SISK: We said we have to have a fire. We have to have that in the ground. They said, ‘Oh no. You can put that in a BBQ pit, but you can’t put that in the ground. It’s like well, then we have to be there 24/7 for 4 days. They said, ‘Oh, no , no, no. You have to put that fire out at 10 o’clock at night and you can come back at six o’clock in the morning and light it up again.’ It’s like, ‘Oh, no , no.’ It’s like once we light that sacred fire, we have to stay over. We have to tend that fire.

CHIEF SISK: And so, after one of those meetings, I went out there and I put tobacco down on the place where the fire was going to be. And the next meeting, we had with the Bureau of Reclamation. They had given us the permit in the name of the Winnemem Wintu Tribe, which is basically recognition of our tribe, right? And they had given us everything we wanted.

WOMAN: Thank you for coming to the press conference for the Winnemem Wintu war dance.

The war dance began on September 12, 2004. The Winnemem Wintu gathered at a grassy area on federal property within view of Shasta Dam’s spillway. News media showed up as did environmental activist Julia Butterfly Hill. She’d gained national recognition when she occupied an ancient redwood tree for two years to stop it from being logged.

JULIA BUTTERFLY HILL: Sometimes it’s very hard to make people understand why issues like this are important when they live in cities, maybe like Chicago, or New York City or a big city somewhere.

BUTTERFLY HILL: A Native elder taught me a beautiful thing and told me, Julia, what some of you would call resources, we call relatives. And so I am here today to call upon the people across America to begin to recognize our responsibility as a sacred responsibility, to protect relatives and to begin to look at the way we use this sacred earth and all that’s on it.

Chief Caleen also spoke before the small crowd.

CHIEF SISK: All right, thank you for coming and for being interested in our situation here.

All of this audio of the war dance comes from filmmaker Toby McCleod, who was there.

CHIEF SISK: We are the Winnemem Wintu tribe of Northern California here and have survived the development of the Americas and the statehood of California.

It’s worth repeating that Chief Caleen Sisk was a relatively new leader at this point. And under her leadership, the Winnemem Wintu were taking on the U.S. government. With a war dance. She told me later, it wasn’t without fear. At the press conference, she spoke of sacred sites threatened by the proposed dam expansion.

CHIEF SISK: We visit and take care of and practice at our sacred sites, all along the McCloud River up to Mt. Shasta

But even back in 2004, salmon were top of mind. Federal agencies had yet to publicly discuss restoring Chinook populations above Shasta Dam. But at the press conference, Chief Caleen pushed the idea.

CHIEF SISK: And so this dance is partly for them, to try to bring the salmon home. People want to see an increased population of salmon. Well, let them go upstream. Let them go up the rivers and they’ll multiply. There’ll be more salmon if you give them back the beds [they] are familiar with. They run here and they stop right here.

CHIEF SISK: No salmon go up to the Pit River Nation. No salmon go up to the Shasta Nation. No salmon come up for the Winnemems. We’re salmon people, all of us, upriver. We’re all salmon people connected to this river. And because we have no salmon, our diets and our health status has diminished. And we suffer from not having the salmon with us.

CHIEF SISK: So today we are here to tell the river, to tell the salmon, to tell the world that we’re still a people and that we have the right for a cultural preservation. And we’re hoping that all the good people of the country, all the good people of the state, the good people that are in powerful positions, will hear us.

For four days and four nights, the warriors danced in front of a sacred fire. They fasted. They never left the grounds, spending the night in sleeping bags around the fire.

It was their first time to perform this dance. But from then on, it became part of their repertoire during big ceremonies. Here’s Rick Wilson, the Winnemem Wintu dance captain, speaking about the warriors’ intentions.

RICK WILSON: He says this is me and this is who I am. And the fire looks them over, checks them out, you know, to see if we’re worthy of that, to be a war dancer for our tribe.

WILSON: But that’s what, one of the things that this dance does it, it brings out the spirit. It brings out the things that are in Mother Earth.

That day at the dam, the young women of the tribe dressed in white. Chief Caleen told filmmaker Toby McCleod they were the water girls. She also talked about the meaning of a song they sang about the landata nur, or the old time salmon.

CHIEF SISK: That song says, “H’up chonas…” It means the warriors don’t like the big water they see.

CHIEF SISK: And then when they say, “landata nur...” It means that we want to, we want the old salmon, old way, old time, big salmon and lots of them come back up. We want to see them again.

CHIEF SISK: And we didn’t know that song two days ago. But did you hear it being sung? It’s as if we knew that for years.

On the fourth day of dancing, a Winnemem Wintu man who embodied the spirit of the bear came out to dance with the warriors as well.

CHIEF SISK: And if you’d said to us a month ago, what are you going to do? What will the dance look like? You know, we were told these things from the Creator.

CHIEF SISK: The bear decided he wanted to come and he decided when he would come in. To give us strength. It’s like that last leg that you’re running. We’re on our last day, which is the hardest for our warriors who are fasting. So he’s lending that strength to them.

What came next surprised Chief Caleen.

CHIEF SISK: Eighty-seven newspapers around the world picked up the story that this small tribe declared war against the United States and danced on the dam.

They included the New York Times and the Associated Press.

To me, this is where the Winnemem Wintu story gets a little fantastical. Like if you were writing a novel, it’s the twist you’d want to make up.

Remember when I told you that Chief Caleen wanted wild eggs from really far away? Well, here’s what that was about. A few months after news of the war dance went around the world, they got an email from a professor in New Zealand. He wrote: we have your fish.

It got the Winnemem Wintu thinking— about how to get them back.

***

A Prayer for Salmon is a project of The Spiritual Edge at KALW Public Radio. Support comes from the Templeton Religion Trust, California Humanities, the Kalliopeia Foundation, Save Our Spirits and The Water Desk, an independent journalism initiative of the University of Colorado Boulder. We are produced on Ohlone and Coastal Miwok land.

Thank you to the Winnemem Wintu and the Run4Salmon community for welcoming us, our microphones and cameras into their midst. To contribute to the Winnemem Wintu’s nonprofit, go to sawalmem.io.