Call this hotline number if ICE is at your door

Bay Area faith groups are taking on immigrant rights with renewed urgency.

By Judy Silber

MARCH 8, 2017 — All over the Bay Area faith groups are stepping up to oppose the Trump administration’s executive orders that could clear the way for massive deportations.

Some are joining a growing network of sanctuary churches where those at risk of deportation could stay indefinitely. Others are offering support like food or references to legal aid.

In San Francisco, the Catholic Archdiocese is also pushing hard to address the needs. Two parishes say they will offer sanctuary. Every week “Know Your Rights” meetings are hosted on church grounds. In addition, there’s another effort afoot: a hotline for people to call should immigration officers show up in their neighborhoods, home or work. The hotline is a collaboration between nonprofits and the San Francisco Archdiocese. It’s funded by the city of San Francisco.

A Bright Idea

The Archdiocese got involved when an idea came to Violeta Roman on her way to a Sacramento meeting of immigration advocates. It was November, and Donald Trump had just been elected. Roman is a San Francisco resident. She’s originally from Mexico. She’s also an organizer. She was sitting in the car, thinking about the very real threat of deportation when she suddenly blurted out, “What if there were an emergency hotline?”

She was thinking of something like 911, that you could use if ICE, the Immigrations and Customs Enforcement arm of Homeland Security, showed up at your door.

“A number,” she says in Spanish. “Where in this moment when immigration is at my house,” you could ask, “What can I do?”

Lorena Melgarejo works for the San Francisco Catholic Archdiocese, coordinating help for the immigrant community. She was Roman’s companion in the car that day.

“We laughed,” Melgarejo says. “And then we were like, ‘Huh, how do you make that happen?’”

Violeta Roman’s vision for a hotline was guided by personal experience. Two and a half years ago, at five in the morning, ICE agents came to her house for her father, who is undocumented. Roman was at work.

“My daughter said they were knocking really hard on the door and said they were police. They never said that they were immigration,” Roman says.

Frightened, her daughter opened the door. The officers handcuffed and took away Roman’s father.

“And when this happened to my father, the first place I ran was my church,” Roman says.

Her priest introduced her to Melgarejo, who helped find a lawyer. Church members went to court with her father. They listened to her. Her father eventually gave up fighting his case and returned to Mexico. Even so, Roman feels lucky. She knows not everyone has access to that kind of help — which is where the hotline idea came in.

It turns out Melgarejo, who was there in the car, was just the person who could help make a hotline happen. She’s well-connected to other immigrant advocates. In addition to her job at the Archdiocese, she works for nonprofit Faith in Action as a community organizer.

“This reality of regular, everyday people being targeted by immigration is not something that just started after the elections,” she says.

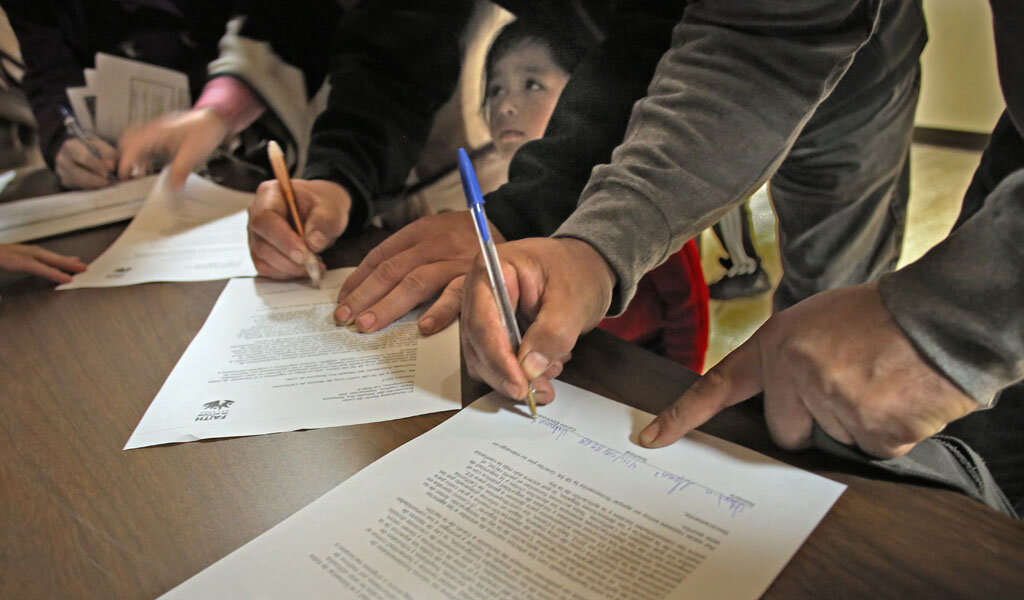

Still, she says it’s a different era. After Trump’s election and executive orders, the threat is higher in San Francisco. A collaboration of nonprofits called the Immigration Legal and Education Network had already begun putting together a hotline. It connected undocumented people who had been arrested by ICE with legal help. Roman and Melgarejo decided to team up with them. The nonprofits had lawyers and city government funds to pay for the hotline. The Archdiocese and its partners could help spread the word. They also began recruiting volunteers who would provide support for families, and witnesses who would physically be there as ICE made its arrests.

“We don’t even know what it’s going to take to stop deportations under this new administration,” Melgarejo says. “But if we don’t know about the deportations in real time, they’re going to be disappeared.”

Melgarejo says she knows this fear from the inside. Her own family lived for years in the U.S. without papers. They came from Paraguay on a temporary visa in 1993.

“Just like when many of us came to this country, we came running away from these repressive governments that would knock at the door and take your dad and disappear him in the middle of the night,” Melgarejo says. “This is the same thing.”

Volunteer Training

On a rainy weekday evening, about 60 people are gathered in the vast cathedral of Saint Agnes Church in San Francisco’s Haight Ashbury neighborhood. They’re here for a volunteer training. Some are church members, others not, but all are inspired to help a community that’s become more vulnerable under the Trump administration. From a podium, Melgarejo asks how many people know someone who was deported in the past eight years. In San Francisco, Homeland Security reported more than 31,000 enforcement and removal operations in 2011. Only a few hands go up.

“In a city that has a huge amount of immigrants, we don’t know one another, we don’t hold one another,” Melgarejo says to the crowd. “This city is too small for us not to know what’s happening to our neighbor.”

This is the moment to forge community connections, she says. Then she tells them about the hotline and how the volunteer part will work. After someone calls, volunteers will go to where that person is — their home or place of work. First, they’ll verify that it’s not a false alarm. If they arrive after an arrest, they’ll connect with the detainee’s family. If ICE is still there, they’ll turn into observers and videotape. They won’t interfere with what’s happening, but the videotapes can be used as evidence in immigration court, if necessary.

“I think initially it feels scary,” says Monica Floyd, who is here to volunteer. ”But I think really it’s just about being there and observing.”

Floyd says she grew up in Oakland, where some of her friends’ parents lacked papers. “And so I’ve had a few friends whose parents have been detained and one friend, their father was deported.”

At the time, she says she didn’t understand the full impact.

“My response was, ‘Oh, that’s awful,’ but I didn’t understand how long-term it was,” Floyd says. “So just learning about it is important, but also figuring out how to be part of the solution is also now far more important to me.”

Being part of a solution is also the intent of Saint Agnes, the church where tonight’s training takes place. Its congregation has few, if any undocumented members. Even so, it has decided to stand up to mass deportations. This is its second volunteer training — the first attracted more than 350 people. It’s also declared itself a sanctuary church, willing to shelter people with final deportation orders.

The Church’s Role

Natalie Terry, director of Saint Agnes’ Spiritual Life Center, is heading up the effort. She says she thinks the Catholic Church hasn’t always done the right thing.

“Because the church hasn’t done historically a good job at responding to the cries of people on the margin,” Terry says. “It hasn’t done a good job with recognizing women’s equality or women’s roles in leadership. It hasn’t done a good job at upholding the dignity of the LGBTQ community. And many, many other communities.”

She says Christian teachings are guiding her church’s actions now to help the undocumented community.

“We look to Jesus to understand who we should be in the world,” Terry says. “And when we look to the Gospel stories, to the stories of Jesus’ birth, of his life, of his suffering, of his death, it’s very clear that Jesus was a friend to all. Open to all people. And this is really important for us to remember right now.”

Members of the Catholic Church played a big role in bringing attention to the brutal Central American civil wars of the 1980s, and the U.S. role in them. But the Church was far from united in its criticism of government policies. Not all priests supported the civil disobedience at the heart of the sanctuary movement, which sheltered refugees without papers on the safety of church grounds.

The California Catholic Conference of Bishops released a strong statement against policies that target undocumented immigrants at the end of February. But individual bishops are divided on how much action to take. In San Francisco, Archbishop Salvatore Cordileone is taking a proactive stance. That includes supporting churches that want to be sanctuary spaces, and those providing other types of support, like the hotline idea.

Know Your Rights

Sunday Mass is ending at the Cathedral of Saint Mary of the Assumption, high on a hill in San Francisco’s Western Addition. But today, many of the Latino congregants will not go home. Instead they’re heading downstairs for a workshop to learn about their constitutional rights.

More than 200 people have crowded into the space, which is standing-room-only in the back. The church’s priest, Father Arturo Albano, begins to speak.

“Good afternoon,” he says in Spanish. The audience laughs and claps when he says that he is of Filipino blood, but with a Latino heart. They laugh again when he says that his dog, whom he holds by a leash in his hand, is from Juarez, Mexico and is undocumented.

“President Trump wants to arrest him,” he says.

Attorney Mark Silverman takes the pulse of the audience. He’s with the nonprofit Immigrant Legal Resource Center, one of the groups that is providing legal support to the San Francisco hotline. He asks people to raise their hands if they have no fear about immigration.

Only a few hands go up. He asks if anyone feels panic. Far more people raise their hands. Then he says something reassuring. He tells the group that for the majority of undocumented people, the risk of being deported is small.

They still need to be informed, he says, and they need to know their rights, such as the right to stay silent if asked for papers, or where they were born. He also says that if detained, they should fight in court. They may not win the case, but it will buy time and by then, there could be a new administration.

During the presentations, an older man in the front row stands up.

He asks in Spanish if there is someone connected to the Mexican Consulate who can speak for him, if he is detained.

Lorena Melgarejo points to a poster behind her. In large print is a number. 4-1-5-2-0-0-1-5-4-8. It’s the hotline, also called the San Francisco Rapid Response Network.

If ICE comes, you can call this number and there will be help, she says. The older man’s name is Francisco, he didn’t want us to use his last name because of fears about his immigration status. He’s originally from Mexico, but has lived in the United States for 17 years. He says he arrived to the meeting worried, but feels a lot better now.

“I feel happy knowing I can get help through people at the church,” he says in Spanish. “Frankly, what we feel is terror.”

But after the meeting, he says he feels different. In a place like this, he’s among friends.

That’s also what Violeta Roman felt when she received support after her father was detained. Now her dream of the hotline promises to help others feel less alone. Lorena Melgarejo says it’s appropriate and important for the church to take an active role. In her mind, this is a spiritual crisis.

“For me, speaking as a person of faith, I’m talking about something that seems immoral,” Melgarejo says. “The Catholic Church, the way the bishops have spoken about it, there is a need, a crisis — we need fix the broken immigration system.”

San Francisco is the first county in the Bay Area to organize a hotline like this, but Melgarejo says it won’t be the last. Already Alameda has launched a similar program. And she’s working to help San Mateo, Marin and San Jose do the same.

* * *

The Spiritual Edge is a project of KALW Public Radio. Funding comes from the Templeton Religion Trust.