How an architect designs sacred space

What is the process to design sacred space?

By Angela Johnston

JAN. 21, 2015—Architecture has the power to transform. A building can make us feel joy, or sadness, powerful or weak. Nowhere is this more true than in a church, a chapel, synagogue, Buddhist temple, or a mosque. For centuries, religion has sparked the design of some of the world’s most beautiful buildings. But what is that process? What built elements make a space sacred?

***

Susie Coliver told me experiencing the design of a sacred space begins way before you step foot in a building.

Thinking outside of the building

Coliver and I are standing in the parking lot of Kol Shofar, a synagogue in Tiburon. We’re surrounded by eucalyptus trees and grassy hills. The building is nowhere in sight. There’s a twisting set of concrete stairs ahead of us. They wind around the trees, taking you forty feet up the hill.

“You leave the parking lot behind. You leave the everyday. You leave the secular behind as you climb, slowly,” Coliver tells me as we walk up the stairs.

She points out the concrete landings. They are imprinted with leaves from trees above. Each landing has a bench.

“It feels very accessible and psychologically that's important, especially for people who are not as agile,” Coliver says.

At the top, the synagogue finally comes into view. Coliver designed it four years ago. She’s Jewish, but has connected and designed buildings for communities of many faiths.

“The hope is that from the parking lot, up the curved stairs, that one is going through a process of quieting,” Coliver says as we make our way into the building, toward the sanctuary’s entry.

PHOTO CREDIT: Tom Levy

“The hope is that from the parking lot, up the curved stairs that one is going through a process of quieting,” Coliver says as we make our way into the building, toward the sanctuary’s entry.

Entering the sanctuary

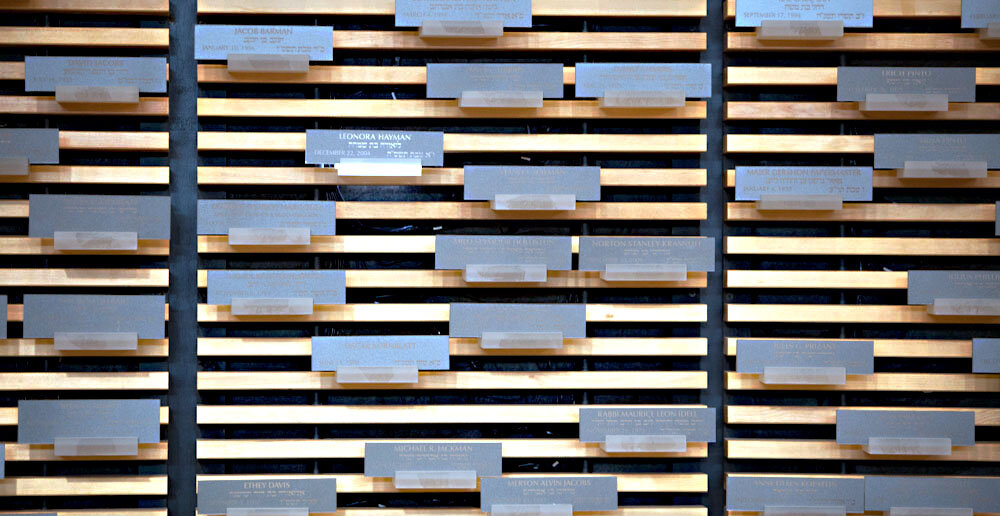

Along with any music, light seeps through gaps in the walls of this curved hallway.

“So not unlike being in a forest, the light is coming through slatted wood. The wood is in variable dimensions so the light is hitting every piece of wood along the curved path a little differently,” Coliver says.

Before Coliver even begins putting pen to paper, she asks a committee of community members a central question, to recall a place where they felt most connected to a spirit beyond themselves.

“It’s very rare that somebody will say a cathedral. It’s far more likely in our experience that they’ll say a place in nature. A sunset on the beach, or they’ll say a mountaintop with an endless view, or they’ll say a grove of trees with dappled light coming through,” she explains.

You can feel this as you emerge at the end of the entryway into an open round space. We’re in the sanctuary now. It feels like the center of a redwood grove. The curved rows of seating are colored with a burnt red fabric, matching bark of the trees nearby. They wrap around the central bema, or pulpit.

“People frequently let out a sigh,” Coliver says.

“I think people feel a small sense of awe. You see it on faces a lot.”

Being in the round

If you were in the sanctuary during a service, you’d see Rabbi Chai Levy in the center and the faces of 100 others.

“When you’re praying, you’re seeing the face of the other, and that divine dwells in that holy space where humans connect,” Levy says.

Levy says as soon as you put two people together, God is in the mix. It’s something the rabbi and the committee wanted in Coliver’s design.

“I see both the beauty of people having prayerful experiences, their souls reaching out in prayers. And then also, you know, I see the faces of people struggling with whatever they’re going through in their lives.”

Not only can people see one another clearly in the round, they can also see changes taking place outside. There’s a tradition in Judaism that the day starts not at midnight and not at daybreak but actually when you can see the first three stars in the evening.

“So we gave them skylights through which you could discern when the new day had started by virtue of being able to see the stars. That was hugely important to them,” Coliver says.

Another important element for the congregation was making sure everyone could hear each other.

PHOTO CREDIT: Tom Levy

“We find that in many of the sacred spaces we are doing now, there is more emphasis put on participation than there is on sitting quietly and listening. The more important the room acoustics become…it’s less a single point of sound and more a communal experience.”

That’s true at Kol Shofar where Rabbi Levy likes to lead interactive discussions. She also likes to lead the community in dancing.

“People holding hands and getting in a line and dancing around so we’re a community that wants to celebrate and feel joy together,” Levy says.

The round space only serves to reinforce this communal spirit. Coliver says it also challenges the idea that the leader is the focal point.

“It’s become much more desirable to erase those boundaries,” she says. “To lower the pulpit so there’s no separation between where people are sitting and where the service is conducted—or very little.”

Symmetry within asymmetry

When you look up to the ceiling from the bema where Rabbi Levy stands, you’ll notice a simple metal chandelier, and vaulted dome, which are offset from the center of the room. Coliver says this asymmetry is intentional.

“If it were symmetrical, there would be a suggestion that perfection is attainable, which we know it is not. We all have struggles, we all have conflict and that conflict is made physical in this space and people feel that very very carefully.”

Rabbi Levy hopes people who come to her services take this asymmetry back outside with them.

“I hope that when people leave the space they feel like they’ve learned something, that their minds and their hearts have been stimulated and challenged and nourished,” Levy says.

Searching for meaning in the mundane, says Architect Susie Coliver, is what spiritual architecture is all about.

* * *

The Spiritual Edge is a project of KALW Public Radio. Funding comes from the Templeton Religion Trust.