Muslim converts wrestle with isolation, seek support

Religion and culture are often intertwined. For converts to Islam, that can lead to isolation.

By Hana Baba

MAY 8, 2017—About 20% of American Muslims are converts — people who didn’t grow up with the religion and often don’t have any cultural ties.

In some faiths, there’s a clear path for prospective converts. Catholicism, for example, has an official course of rites, rituals, and classes for those entering the Church. Islam doesn’t have a formal conversion process like that. To become a Muslim, you declare your new belief with conviction in front of a Muslim witness, and that’s it.

For this reason, many converts say they need help and support — but it can be surprisingly hard to find. One place it can be found is the Muslim Community Association in Santa Clara, which has been offering post-conversion support classes for the last seven years.

Twenty-six-year-old Nathalia Costa is in the women’s prayer hall at the mosque. She’s here for the midday Saturday prayer. Wearing a baby blue headscarf, she stands in a straight line with her hands folded above her heart, moving in unison with about 20 other women. They kneel, then prostrate, then sit, and stand back up again, all in silence. Through the corner of her eye, head bowed, Costa follows the women closely.

Costa is new to this. She’s a Brazilian American who became Muslim in December 2016. She used to be Catholic, and says her conversion to Islam came after a long search. She tried different churches throughout her life — from Catholic, Presbyterian and Baptist, to Seventh-Day Adventist Christian congregations.

“And I remember asking my mother,” she says, “‘How do I know what is the truth if every church is saying something different?’ [My mother] said, ‘You don’t know, but whatever you feel in your heart to be right is the truth.’”

Costa started studying other religions like Islam and Buddhism and moved to Istanbul, Turkey, where she taught English for a year. While there, she was further immersed in Islamic culture.

“I learned more and more about it, and I found the truth in Islam. I found that there’s a lot of consistency in it,” she says.

Now, Costa is learning these new rituals little by little.

She laughs, “I get jealous of people born into the religion.” She says she still doesn’t know how to pray correctly, still needs to learn all the suras, the chapters of the Quran that Muslims memorize to recite in prayers.

When the prayer’s done, the other women notice her: an unfamiliar face. She tells them she’s a new Muslim, and they crowd around her — all smiles, hugging and kissing, congratulating her. Especially excited is a Moroccan grandma named Sister Fateeha Abu Mahmoud Kratas. She hugs Costa and says, “You will be our daughter! You are very, very, very welcome!”

After Costa emerges red-faced from the big dose of warm and fuzzy welcome, she walks to another mosque building for her convert support class. It’s called “Study Islam.” She says she’s slowly learning about the religion, but there’s a lot she still doesn’t know. It feels good to be around fellow converts, learning more information and being able to openly ask questions.

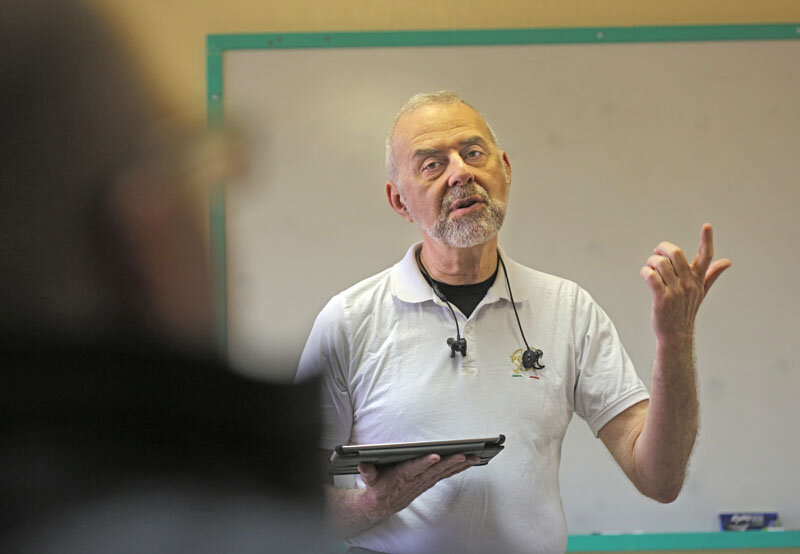

In class, instructor Tarek Mourad teaches the new converts about Islam’s main tenets and rituals. Today’s class is about sinning and forgiveness.

The students are attentive as he instructs: “The whole concept of original sin — it doesn’t exist. Because Adam and Eve were forgiven before they left the garden of Eden, so they did not carry down with them an original sin to atone for. It’s not a state of being. A sin is an act that you do.”

The class also tackles topics specific to converts. Nathalia Costa asks if it’s okay for her to participate in holidays like Christmas, to be part of her family.

Mourad answers, “You are part of the family. You should be there. You’re not going to worship that way, you’re not going to eat the ham, you’re not going to drink wine.”

Costa laughs, visibly relieved.

Mixing up culture and religion

These topics don’t normally come up in your average Friday prayer sermon, where the target audience is, for the most part, Muslims born and raised with the religion. For them, strong cultural backgrounds influence how they practice. It’s another hurdle that converts have to navigate.

Instructor Tarek Mourad says one of the biggest problems people have is mixing up culture and religion. In his class, students sometimes come confused about things they hear are Islamic, but are actually part of a certain culture: mostly Arab, South Asian, Afghani or Iranian.

Examples he gives are the Saudi Arabian practices of totally segregating women from men, or not allowing women to drive. Saudi Arabia is the birthplace of Islam, and houses its two holiest sites.

But, Mourad says, “the problem with a place like Saudi Arabia, because of the influence it has, the money it has and the oil it has, people tend to think that this is Islam. [But] Saudi Arabia represents a very small portion of Islam.”

American converts complain of feeling shut out of the mosque environment because it can be so steeped in cultures they don’t belong to. They vent in blogs and podcasts like Islamwich. The American women bloggers discuss convert life, including calling out Muslims who want to impose their cultures, like in this excerpt:

And please: Stop asking converts if they know how to cook some dish from your country or dessert your mother made back home. This doesn’t make anyone more or less Muslim. This is your culture! Stop telling newly converted Muslims that they must wear the thobe, abaya, or a shalwar khameez, because “this is how Muslims dress.” This is your culture!

That alienation is one of the reasons the Muslim Community Association has this class. Out of more than 80 mosques and Islamic Centers in the Bay Area, only a handful offer formal classes for new converts. Instructor Tarek Mourad says class sizes here have been small but steady for seven years running. This is a more diverse mosque than many, and that can also help new converts choose how to practice Islam in their own way.

“We have people from all over the world,” Mourad says. “We’re not one school of thought. We have at least 30 or 40 different countries of origin here. So we’re very diverse, and we treat each other that way — with respect of our diversity.”

But this is not that common. Many mosques are casually known by cultural labels: the Yemeni mosque; the Afghani mosque; the Pakistani mosque. So new Muslims can feel isolated. Friends and family don’t understand their new religion. And bridging cultural differences isn’t easy. That can push converts to look for connections on the web: through social media, dating sites, podcasts, and YouTube videos.

Isolation and community online

A YouTuber named Missi1 fights off tears as she describes how she feels.

“It’s been really difficult,” she says. “ I just have no one to talk to who would not judge me or disown me or take me seriously about it. A lot of people are like, ‘You’re a pale-ass redhead, what you wanna do with a Middle Eastern religion?’ I wish I had the strength to go into a mosque and say I need help. I don’t know where to go from here. I wish I did.”

Being a convert can be a lonely existence, but relying on the Internet can also be risky. Hours and hours of being online alone can expose new converts to more non-mainstream, hardline materials. And they can encourage what some say is a skewed understanding of the religion — things like how to marry, what to wear, what to watch or not watch. A video by a popular Australian sheikh shows him berating parents on letting their children watch Harry Potter films, saying they “promote paganism and evil.”

But it can be much more serious than dissing Harry Potter. Studies show most violent extremism in the West is committed by converts. ISIS has been known to recruit these often-vulnerable, isolated new Muslims.

Convert classes or support groups get people off the internet, in community, and in conversation with real people, like in the Muslim Community Association class.

Instructor Tarek Mourad praises his students. “Everybody coming through this is genuinely intelligent and critical and thinking,” he says. “They’re not somebody that just follows just the normal average political opinion or the opinion they hear on the radio or something like that…They’re actually focusing on learning and understanding at the root level.”

Embracing the new

Still, it isn’t easy. Converts are embracing a whole new religion, with all of its practices and obligations — like regular prayers and fasting during Ramadan. Add to that a negative societal view of Muslims, and for Nathalia Costa, deciding to wear a hijab.

In addition, they have to navigate how their families feel. Mourad says some families disown their kids. Others constantly debate them and challenge them. Many are hurt and offended their child would leave their own spiritual tradition. Others are afraid of the prejudice Islam may bring with it.

Nathalia Costa says she dreaded the day she’d have to tell her Catholic parents. She says it caused her a lot of anxiety.

“I found it similar to what I can imagine it would be for someone who is homosexual coming out of the closet,” she says. “I would spend nights crying, like my family is going to hate me. How am I going to go about this and just kind of building up to it. I was like preparing for a war.”

When she did tell them, her mother was accepting and understanding. Costa adds, “Some people in my family, I don’t think they were very thrilled to hear that. But at the end of the day they were accepting, and I think that was the most important thing for me: to know that they still loved me for being a part of their family, and didn’t kind of abandon me, which I think unfortunately some people go through.”

But she still has some challenges.

“I’m Brazilian!” she says. “It’s not something they’re accustomed to. You know, family get-togethers is like hanging out by the beach in your bathing suits, drinking and eating. And I’m not going to be able to partake in that necessarily. And so I don’t want to be looked at as ‘the other.’ But you know, it’s going to be a journey to kind of convince them that I’m still me.”

Instructor Tarek Mourad says family is one of the hardest parts of conversion, that needs the most support. He tackles it straight on in his class, including how to address parent fears that the new religion will create distance between them and their children.

This class is especially important for those who face rejection at home because he says, “it builds a family for them. It builds a space for them to find strength and common experiences. If somebody has been rejected by the family, to find somebody else in the class who’s been rejected, and they kind of get some tips and ideas from them on how to deal with it.”

In class, Costa asks if it’s okay to give gifts during Christmas. Mourad answers by quoting a saying by Islam’s Prophet Muhammad.

Tahaadu Tahhabu means, he says, “Give gifts. You bring your hearts closer to each other. Give them gifts inside of Christmas and outside of Christmas! The difference your family has to see with you when you become a Muslim is what? You love your parents more. You’re more obedient to your parents than you were before. That will say volumes.”

As class winds down for the day, Nathalia Costa says the challenges continue, and sometimes she feels lonely, so she’s grateful for this class.

“I’ve been going through a lot of the journey kind of on my own,” she says, “It’s been sometimes a little bit isolating, so being around other people through that is really refreshing.”

For Tarek Mourad, that’s what it’s about. Not just welcoming new Muslims, but sticking with them on the long, often bumpy, road ahead.

He says, “It’s a journey that they’re going to go through for the rest of their lives and they grow, and that’s what I love seeing. I love seeing that in their eyes. It just makes me feel very happy.”

* * *

The Spiritual Edge is a project of KALW Public Radio. Funding comes from the Templeton Religion Trust.