Becoming Muslim: RABI’A

Who says women can’t lead prayer?

Listen and subscribe to The Spiritual Edge wherever you listen to podcasts - Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Google Podcasts.

By Hana Baba

“We need to have a different setup for worshipping,” Rabi’a Keeble says. “One that makes it clear that women are not second class citizens, that women are equal to men.”

As far back as Rabi’a Keeble can remember, she was interested in religion and the Bible.

She laughs as she tells a story her mother told her from her childhood.

‘‘A repairman was in the house doing something. And he was flirting with my mother because my mother's very pretty. And I heard it. I was in the other room and I came out and I said, ‘You're not supposed to covet. You’re coveting my mother. You're not supposed to covet your ox, your ass, your neighbor's wife.’”

“That's as much as I could remember of what I read,” she says. “And they both just cracked up. They were like rolling on the floor that I'm standing there like some prophet, you know? ‘You're not supposed to flirt with my mom.’”

It’s a funny story, but it also shows Rabi’a’s early sense of rebelliousness, and her tendency to think for herself. That same spirit emerged decades later when she was becoming Muslim.

She was going to Friday prayers in Oakland back in the 1990s. Early on, she started noticing something that bothered her. Usually after the prayer, there’s a time for the Imam to talk to congregants and answer their questions. But there was a problem.

“I couldn't talk to the Imam in the mosque,” she said.

“It's like, men could talk. Men talk to him all the time. He'd be standing up there. They'd be laughing at some joke. Men would talk to him. Women? No.”

Like in many mosques, the Imam was at the front of the prayer hall. The men were right behind him. And the women sat behind the men.

Men, she says, were allowed much more openness and leeway to grow their understanding of Islam. “If I can ask a question and I can get an answer then I can grow that much more,” she says.

Rabi'a was new to Islam and was thirsty to learn from the Imam. Her frustration built. This lack of access to the Imam, it irked her. She felt her access to God was being limited, too.

“I just got very frustrated with it. The idea that because I'm a female, I can't talk in God's house. Because I'm a female, I have to sit back here where even if I did speak, no one's going to really hear me.”

“The whole thing implies I'm not worthy. We're going to sit you in back with all the squalling babies and all the gossiping aunties because we know you're not paying attention—because you're a woman.”

A question turns into action

Rabi'a grew more and more discontented with the mosque. A thought started to form.

“I just started to conceive of a learning space, of a worship space that was absolutely friendly to women, that would give women the advantages of growth. Spiritual growth. Intellectual growth.”

So Rabi’a made a plan, got a little grant and in 2017, she launched a women-led mosque in Berkeley. She welcomed anyone who wanted to join, no matter their gender. A local seminary gave her a room where her first service was held.

Her plan was to teach her congregation how to do Juma (the Friday prayer); how to lead prayer; how to call the Athaan (the call to prayer). How to give a khutba (the sermon) and all the liturgies of Islam.

“So we started getting to the point where some ladies went and studied at home, and came back and were able to lead prayer. They had never done it before and they did it beautifully.”

After the first service, Friday prayers were held every week with the sermons given by women. Guest speakers were women and the Imams were all women. She named the mosque Qalbu Maryam, In Arabic, it means the heart of Mary. It’s in reference to Mary, the mother of Jesus, who’s held in such high regard by Islam that she is the only woman mentioned by name in the Qur’an.

Hind Makki is an interfaith educator with the Institute on Social Policy and Understanding in Chicago, which commissioned a study on mosques called Reimagining Muslim Spaces. She says in the last 15 to 20 years many convert communities started to create their own mosques and their own ‘third spaces’.

She says third spaces are not necessarily mosques, but they’re centers for Muslim community building.

Makki and her team consult with mosques on how to be more welcoming to women. She says converts tend to launch new spaces based on what they’re missing in mainstream mosques- whether it has to do with gender, or language, access to learning, or just belonging.

And one of Rabi'a’s biggest issues- access to learning from the Imam— Hind Makki says it wasn’t a problem in the Prophet Muhammad’s mosque 1,400 years ago, and it shouldn’t be a problem today.

Makki says the Prophet Muhammad would give lessons before and after prayers, and women would be there.

“Women would talk and engage with him, and ask him questions,” she says. There was even a time when some women thought that the men were hogging him and hogging his time. They complained, Makki says, and he responded by setting aside an entire day for them.”

Ironically, in 21st century Berkeley, California, Rabi'a’s challenge to the mainstream didn’t go over well. She likens it to being in labor with a child. “One part of me didn't want to do it. Because I knew what was going to happen. I knew I was gonna be attacked. I knew that people who were not comfortable with themselves would feel uncomfortable with me, and judge me and critique me and attack me. And it happened just like that.”

Always curious, always questioning

Rabi'a was born to a Black Christian family in the midwest. She grew up in St Louis, Chicago, and Ohio. Though her parents weren’t really religious, she was surrounded by Christianity through her extended family and community. And there was that Bible in the house.

Rabia especially had this curiosity about who Jesus was. “Black people have this thing about kind of elbowing God to the side. But Jesus, you know, becomes like everything. And I was like, ‘Well, who is this Jesus?’”

“That is kind of a hallmark of who I am,” she says. “I don't buy stuff just because somebody's selling it…I'll look at it. Then I'll figure it out.”

There were a couple of things that especially bothered her. She says the whiteness of Jesus, and the maleness of the Christian God didn’t sit well with her.

That skepticism makes sense when you consider what Rabi'a would have faced as a young Black woman making her way in the world. During college, she joined friends on a road trip to California and ended up staying in Berkeley where she found a job at a law firm.

“I remember being so immature, so green,” she says. She recalls a particular experience. “I was working in this office and all these Caucasian ladies are there and they're the legal secretaries. They have their certificates and legal secretaryness.”

“And I'm just this little Black kid in the front, you know, doing my thing.”

Even though this was California, and this was Berkeley— a place famous for progressive politics and supposed racial harmony— Rabi’a got a rude awakening. Those legal secretaries gave her a hard time.

“They said I smelled bad. They would put bars of soap on my desk. They would do all sorts of horrible things to me.”

Those racist experiences planted a seed in Rabi’a, the seed that would grow into a career involving civil rights and social justice work. She left that law firm, went through a number of other jobs and ended up in nursing, which she practiced for years. But throughout, the one constant was her love of the Bible. And she was still pondering and wondering about God.

She thought ‘Well, the larger part of the Bible is the Torah. I need to study with a rabbi. I want to really understand what's in this Bible from top to bottom.’ Rabi’a did end up studying with a Rabbi and eventually converted to Judaism.

At the time, she was spending a lot of time at the library in Berkeley, reading about social justice, history and spirituality. One day at the library she saw a flyer for Sufi healing.

A Sufi spark

Sufis are Muslims who follow Sufism, a mystical movement within Islam. Its dedicated followers are members of certain fellowships called Sufi orders. Sufism focuses on inward reflection with the goal being forging a direct relationship with the Divine. Being Sufi can overlap with being Sunni or Shia Muslim. They follow a leader—a sheikh—study under them, and engage in mystical worship practices like deep meditation, trances, and dhikr, repeated melodic chanting the name of God. Dhikr means remembrance of God in Arabic.

Many people may know about Sufism from the poetry of Persian Sufi poet Jalaluddin Rumi and from images of the whirling dervishes of Turkey. Rabi’a knew none of this. All she knew was that she was curious about this “Sufi healing.” The class on the flyer was held at the Graduate Theological Union in Berkeley and she went.

In this religious group there was an idea of God that was new to Rabi'a.

“I began to learn and understand that there is this other approach to God, of loving God like you would love a lover. I never heard of that before,” she says.

Rabi’a was enamored by the concept.

“I thought, yes, yes, that's how we're supposed to love God. We're supposed to love God like we love a lover. Longing, you know. Like, ‘Oh, I want to talk to you so bad. I want to hold you so much. I can't eat. I can't sleep unless I have you.’ That's how we're supposed to love God. And I thought this is wonderful. This is what I've been looking for.”

But Rabi’a was Jewish now. What did that mean? Wasn’t this a conflict? Did she have to renounce Judaism?

She thought to herself, “Essentially, Judaism has laid the foundation for me to understand and enjoy and love Islam because Islam and Judaism are not miles apart. They are inches apart. Just as Christianity informs a lot of what is in Islam. So I didn't feel like I had gone really anywhere. I had just stepped through a doorway and that was it.”

Rabi’a knew she wanted to learn more about Islam from this Sheikh’s teachings. One day after class she asked her friend to take her up to him. His name was Sheikh Hisham with the Naqshbandi Sufi order.

What came next was a mystical experience.

She says, ‘‘She took me up to him. And I'm standing in front of him and I'm looking at this man. Now I believe in mysticism. I've seen a lot of things. I walked up to this man and he had like a glow around him. I didn't know him. I didn't know anything about him, but I saw this as I was standing there. I wasn't impressed as much as I was mystified.”

He asked her if anyone had put her up to this, or if she indeed came on her own. “I said, ‘Yes.’’ He said, ‘Then take my cane.’ And I held it. And he started to pray. He started to pray. And he prayed a long time. To the point where everybody was looking around and going, ‘Well, when is he going to give her shahada?’”

Shahada is the attestation of faith for a Muslim. “He says, ‘You repeat it after me.’”

Rabi’a was now Muslim. And one of her favorite parts of Islam was that ritual— dhikr. Dhikrs were held every Saturday night at the seminary.

“I never missed one. You commit this time to simply sitting and chanting and remembering God's name, The parts of God, and just like letting your heart explode in love and worship of God for hours with other folks. And it's wonderful. It changed me. It mellowed me. It did all kinds of things to me. This is a mystery. It's a mystery.”

Rabi’a would start coming to the mosque for services—Friday prayers and dhikr. She met lots of new friends, but something bothered her. That lack of access to the Imam and having to sit in the back of the prayer hall.

“The one thing I had a problem with was: we need to have a different setup for worshipping,” she says. “One that makes it clear that women are not second class citizens, that women are equal to men.”

A drive to seek truth

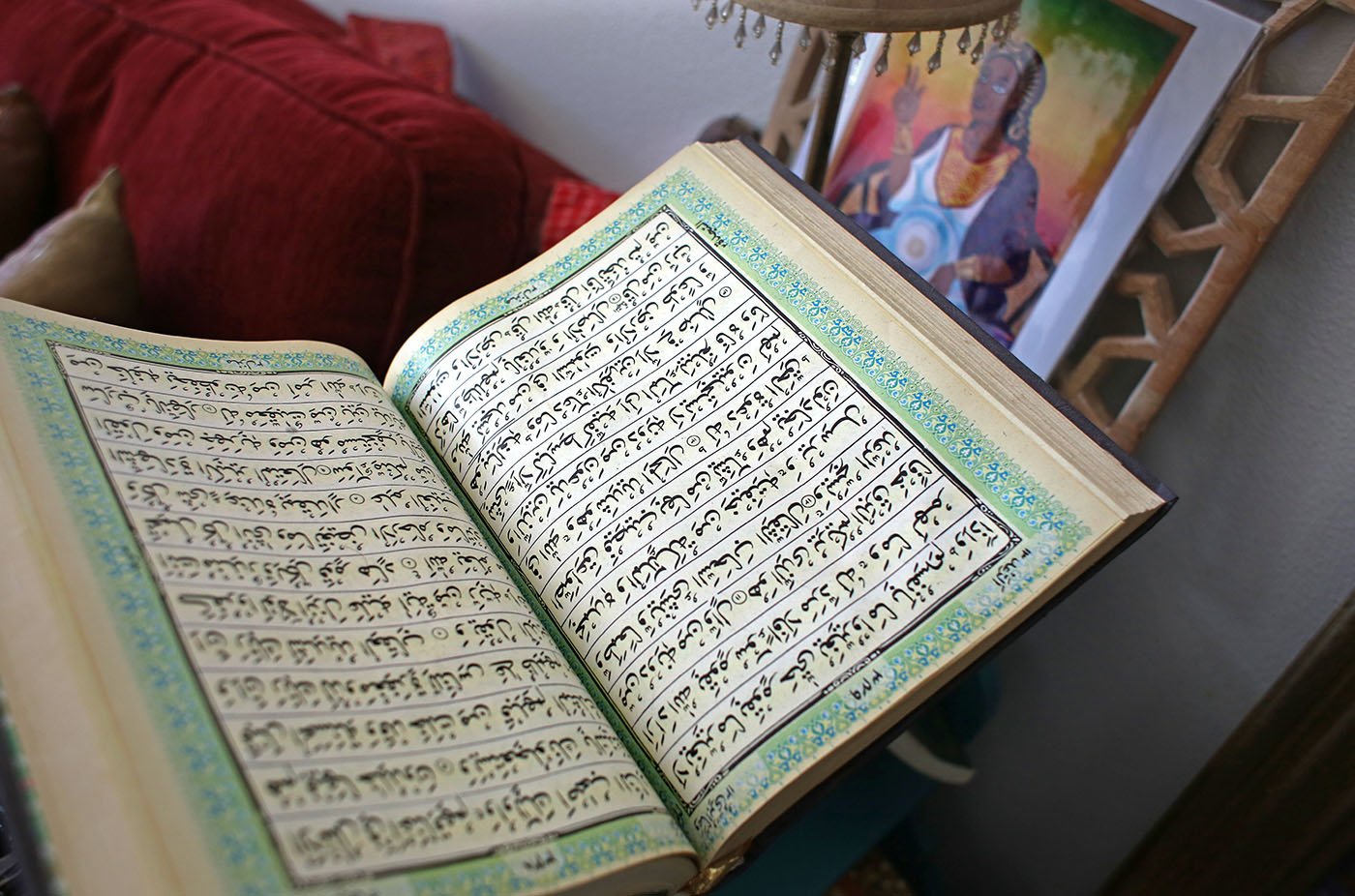

Rabi’a began studying Islamic theology at Berkeley’s Graduate Theological Union. That’s where she first met the sheikh. She immersed herself in the religion and to her, the texts she was studying at school didn’t jibe with what was happening at the mosque.

In many verses, the Quran asserts or alludes to the notion that men and women are spiritual equals, but it seemed that Muslim practice had often veered from that. To Rabi’a, what was happening was something that often happens to religions where a faith is practiced differently by different cultures. A Muslim in an Arabian village will probably practice some things differently than one on the South Side of Chicago. And like at her mosque, many mosques in the U.S. are led by immigrant Imams, people who are born, raised, and taught in societies where gender segregation is the norm in religious settings.

“I understand that some people see modesty and chastity and preserving the feminine Muslimah in a certain…encased in amber. And she must be this way. No, no, no. There's many different ways to be a Muslim woman.”

Qalbu Maryam, the heart of Mary

Rabi'a founded her women-led mosque Qalbu Maryam in April 2017.

It was a big deal. The Mayor of Berkeley showed up. Local media turned out. A woman, Soraya Deen, a Muslim lawyer and activist, gave the first sermon. Deed does interfaith and women empowerment work in Muslim communities. She met Rabi’a on Facebook, and they hit it off.

“Like me, she (Rabi’a) was sick of the patriarchy. She was sick of men telling us what to do, what to believe, what to wear. So then this was burning in her and we were talking about this…You have the agency with your God. You have a right to talk with him.”

Deen remembers that first day excitedly. The night before, she went to Rabi'a’s to stay the night. They talked all night.

“it was very, very exciting. And there were so many people who came— men and women together. And we created a sacred hallowed space and Rabi'a just worked so hard for that,” Deen says.

Rabi’a was on the news, in the papers with images of women in headscarves leading prayer. This was the second women-led mosque in the country, but it was the first that also welcomed men.

Rabia says a lot of women came because they thought it was just a women's mosque. “And I let them know”, she says, that, “I cannot repeat the mistake that patriarchy has taught us. We separate nobody here. That's segregation. Just like the civil rights movement. Segregation means that I think I'm better than you.”

Some women did eventually leave as men were also joining the congregation.

“A lot of the men I spoke to believe a hundred percent that men and women should worship together.”

“One man told me, he said, ‘I like this idea. I don't ever want my daughter to feel that she's subservient to any man’. And he was bringing his daughter.”

Rabi’a’s congregation was also culturally diverse, a hallmark of those third spaces Muslim converts can create. Mosque researcher Hind Makki talked about it.

“These mosques are as diverse as the Muslim population is in the US,” Makki says. “If you go into a mosque in most cities or small towns in the U.S., you don't actually see that racial diversity, except for a very few, a handful of mosques that really reflect the racial diversity of the national community. But in these women-led spaces, whether it's an all-woman space or mixed-gender space, you see that racial diversity. And so the first thing I gleaned from that is that people from all different backgrounds are wanting something different from what the mosques are providing them.”

For Rabi'a, that ‘something different’ was the mysticism, the thoughtfulness. But there was something else. When Islam came in the 7th century, it brought with it new ideas. It shook things up. At the time, it was daring and disruptive to the status quo. Prophet Muhammad came with new social rules that were challenging to the traditions of the tribes of Arabia. He was persecuted so badly he eventually had to flee his hometown.

Rabi'a was shaking things up too— and had to face the consequences.

Challenging times

Some Muslim groups and scholars were quoted as saying that Qalbu Maryam wasn’t a real mosque. That it was blasphemous because men and women shouldn’t be praying together. Or that it’s un-Islamic for a woman to lead prayer when men are present. One Berkeley scholar accused her of being ‘provocative’ and ‘antagonistic.’

Then in July 2018, Rab’ia received a notice from the seminary that they needed the room for classes. She was asked to leave after just a year and a half. She was devastated.

The seminary— known as the Starr King school— says it was a resources issue. But innovative reform mosques like Rabi'a’s have had a hard time finding and keeping spaces. The same has happened to mixed-gender mosques in Europe. Oftentimes, Muslim leaders speak out against them. They struggle to grow their congregations. Funds dry up, and they end up shrinking to small operations just like Rabi'a’s experience with Qalbu Mariam.

In Rabi’a’s case, there is also another thing to consider, according to Kayla Wheeler, a scholar who studies Black Muslims in America.

“When I heard a Black woman founded it, I wasn't surprised at all,” Wheeler says. “I think even when a Black Muslim woman breathes, she's going to face criticism. We're constantly policed in the United States regardless of what we do. But when you decide to threaten the status quo. Yeah, it's going to be met with resistance and sometimes a lack of support from the very people you're helping or supporting.”

Wheeler argues that being a Black Muslim woman has a lot to do with Rabi'a’s shunning by mainstream Muslim leaders. She says you can't disconnect that push back from anti-Black racism, and the unique misogyny that Black women experience.

“I think there's special vitriol that is reserved for Black women who dare to speak out. And I think that just has to reflect the anti-Blackness that you see in a lot of Muslim communities.”

Wheeler says there's often an attempt to create a unified image of what Islam should look like, and who should represent Islam. “And if we're keeping it real, that's usually brown straight men and or white straight men. And so when you have women challenging that, you're challenging those men's authority. And people who are interested in power are going to resist that.”

Wheeler is reminded by the case of Muslim feminist scholar Amina Wadud who made headlines in 2005 for leading the first mixed-gender prayer in America. Wadud was met with threats.

Plus, Wheeler says, the role Black women played in growing American Islam needs to be remembered and revered.

“If you look at how Islam was re-established in the United States in the 1900s. It would not have been possible without Black women who took on public leadership roles,” she says.

She points to the women of the Nation of Islam, once led by Elijah Muhammad and Malcolm X.

Wheeler says, “Claire Muhammed, we oftentimes think of her as just Elijah Muhammed's wife, but she helped run the organization while he was in prison. She was the de facto leader. She helped build the religious schooling. You look at Ella Little Collins, Malcolm X's older half-sister, she helped fund Muslim education. Dr. Betty Shabazz and her role in education, and how those things for them were rooted in Islam. And rooted in this idea that women have the right to take up public space and be leaders and help guide the community.”

She says people are doing a disservice to the very women who made Islam in the United States a possibility when they reject women leaders such as Rabi'a Keeble or Amina Wadud.

Reinvention

Rabi’a ended up leaving the seminary and did lose some of her congregation. She gathered the ones she still had and did another innovative thing: a pop-up mosque. She would book spots and rooms in various places and hold services there. The next year, a church in Oakland invited her to use a room for her Friday services.

But at this point, Rabi’a’s finances were suffering. Her grant money ran out.

Years later, when I ask Rabi’a where she goes for Friday prayers, she says, “Nowhere.”

“I don't go anywhere. I don't go for Juma. I can pray anywhere. I don't go to juma because I refuse to sit behind men.”

She did go once, to an Oakland mosque when a rabbi friend invited her to sit in solidarity after the 2019 shootings in New Zealand.

She went and sat in the front row.

“I wasn't protesting anything. I just felt like I sit wherever I want to sit. And the Imam who I actually know, who I admire…When it came time for prayer, he walked up to me and he said, ‘Sister.’ And he said it really loud. The room was full of people. ‘Sister for prayer, you're going to have to move.’”

“I'm not moving anywhere.”, she told the imam. “I'm a Muslim. I can sit wherever I want.”

He turned around, he walked away.

“I sat there and prayed in the front row,” she says.

She says the men on either side of her didn’t move. They stayed there and prayed.

Today, Rabi’a Keeble continues her work. She’s a scholar of Islamic theology and leadership, social justice and Black religions. Her life is full of speaking engagements, sermon requests and interviews. She’s an author, artist and poet.

Rabi’a story is one of constant reinvention. The Qalbu Maryam story didn’t end with the mosque. She now calls her organization Qalbu Maryam Women’s Justice Center, labeling it a “sacred space for social justice.” She has also launched a group called Muslims for Black Lives Matter. They’ve join marches and solidarity actions around the San Francisco Bay Area.

She holds her sermons online. She doesn’t have a mosque, but Rabi’a says she doesn’t need one to do God’s work.

When I ask her if any of what she went through made her think about leaving Islam, she says, “I'm like these people who are married for like fifty years. They'll never be divorced. I'm not leaving Islam. I love Islam. And God allows me to weather this storm. God never said there wouldn't be storms. But God promises to get us through it. And never once did I think about giving up. I just believe God will bring you through. He will bring you through.”

***

Hana Baba is the host of Becoming Muslim. She also hosts KALW's award-winning newsmagazine, Crosscurrents, and The Stoop podcast: stories from across the Black diaspora.

The Spiritual Edge is a project of KALW Public Radio. Funding for Becoming Muslim comes from the Templeton Religion Trust.