Becoming Muslim: TYSON

Reclaiming a lost heritage

Listen and subscribe to The Spiritual Edge wherever you listen to podcasts - Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Google Podcasts.

By Imran Ali Malik

“In my young mind, the most powerful image or representation that I saw of blackness and an unapologetic revolutionary approach was that of Malcolm, and Malcolm was amazing. And still is to this day. And so the calculus in my mind was whatever produced him, I need to be connected to.”

From a young age, Tyson Amir’s family knew he would become Muslim. He’s been determined to follow the revolutionary example of Malcolm X since he was 10 years old. Islam for Tyson is about walking in the footsteps of Black Revolutionaries, beginning for him with his great-great-great-grandfather, an enslaved man who, according to family lore, was Muslim.

“I don't focus a lot on what might or might not happen. We all go and die. It's just the reality of the situation, but how are we going to live? That is something that we do have some control over.”

This is Tyson Amir, an Oakland-based rapper, writer, and teacher. His path to Islam came out of the Black American experience.

“Although I didn't have what people would consider traditional religion in my home, I'm surrounded by religious practices. The black experience. There's a spirituality to that.”

Tyson is talking about the Black American revolutionary spirit of the 1960s, but also, his ancestors.

The book that is a family treasure

Tyson is carefully handling a large book. It’s a family treasure.

“This is the book that chronicles my family history on my father's side. So the title of it is History and Genealogy of Bartlett and Rhoena Flemister.”

Bartlett and Rhoena were Tyson’s great great great grandparents. The bulk of what Tyson knows about his family history comes from the book he’s holding. It was put together by his extended family in the early 1980s.

Hundreds of people are listed in this book, all of whom trace their lineage back to this couple. It’s hardbound with green leather and embossed with gold letters. There’s a subheading in quotations that reads “I want my blood there on judgment day.”

That’s was they say Tyson’s great, great, great grandfather would always say. It was his tagline.

Tyson believes these words expressed his ancestor’s longing to see justice for the crimes of slavery. The book is full of pictures and archival documents, and it begins with the harrowing tale of how Bartlett and Rhoena Flemister, survived slavery.

"This is a very important story to me,” he says and then recounts the history of his ancestors.

“In the late 1850s Dr. Sweet, a calculating enterprising businessman as well as a doctor, realizing a war between the States was an eventuality, begin to sell his slaves. He sold Rhoena and their oldest son, Charlie for $1,500 to a plantation owner from Alabama.”

“Charlie is my great, great grandfather,” he tells me. “So he separates my family right before the start of the Civil War.”

For years Charlie and Rhoena remained separated from Bartlett and the rest of the family. When they were all eventually freed in 1863, Rhowena and her son walked from Alabama back to Georgia, and by asking directions to the Flemister plantation, found their family again.

“So then as the pages of the book go, here's the ancestry of Charlie Flemister,” Tyson says. “So he had 13 children. I am a descendant of him through his eighth child, Henry Luther Flemister So this is my great grandfather.”

We sit for about an hour looking through the green book. I start to wonder how knowing this much about your ancestors’ struggles would affect you as a person.

“I can't tell you how many hours I've spent in this book,” Tyson says. “Because it meant, and still means, that much to me.”

“I am waiting to be able to take this book from my father. This is my book.”

Bartlett and Rhoena's story survives because they lived to see emancipation and were able to prosper as free men and women. And their story continues to inspire Tyson and the rest of his family.

They acquired land. They fought to protect other people in the community. They were soldiers, bro. I come from that. That’s dope, that’s deep.

And then there’s the detail in the book that is part of the reason we’re telling you this story. By the family’s account, Bartlett Flemister was a muslim. This is remarkable. There were no mosques in the US until the 20th century. It’s only recently that historians have begun to uncover the history of Islam among enslaved Africans here. And yet Tyson’s family book shows that Islam, at least as an idea, did pass down through the generations.

“I come from that and that's such an important thing,” he says.

“There's no way for us to really verify that, but that is the way that the story has been passed down to us,” Tyson says. “The fact that my family has maintained that my great, great, great grandfather practiced Islam, that is important. I'm inspired by that.”

Tyson and I are both part of a larger Oakland Muslim community, but before this story, we hadn’t met personally. I called him up and told him I wanted to do a story about his conversion to Islam.

He warned me that his wasn’t a typical convert story. I guess he meant the kind where there’s a single moment when everything changes. That’s exactly why I was interested, I told him.

Unlike Tyson, I was raised in Islam, the son of Pakistani immigrants. It wasn’t till later in my life that I decided to formally study the faith.

As I met a diverse group of Muslims, I grew fascinated by the many paths people take to get to Islam and started investigating convert stories for my own podcast.

A lot of times, those stories reflected my own; a personal, individualistic spiritual path. But Tyson’s journey tells a different story entirely. One that has everything to do with the experience of being black in America.

Sinbad Avenue in San Jose

“Sinbad Avenue. This is where it started,” he tells me.

He takes me to the neighborhood in San Jose that his parents moved to in the late seventies, just before he was born. It’s also where Tyson first encountered hip hop as a kid.

“This is where all of that began,” Tyson says. “This was where I started rapping, break dancing, all that out here.”

Tyson is wearing his usual outfit. Black pants, black shirt, black beanie. And his custom varsity jacket. The street is lined with modest bungalows with short driveways.

“I remember seeing folks with linoleum out, like putting that on the ground and then pop — locking, breakdancing, back-spinning, all of that right here.”

“And then the older cats here, they rapping and breakdancing. So we got it all from what we saw around us. And then we doing our little kids stuff too, running around playing,” he says.

Before they moved here, his parents were activists in Oakland. San Jose was where they chose to raise Tyson and his older sister. They were one of the only black families in a mostly Latino neighborhood. His father taught at the local school and his mother worked at a dentist office.

Tyson and his sister spent a lot of time with the elderly neighbor across the street. It was pretty idyllic until the crack epidemic hit.

“We didn't ask for it,” Tyson says. “This stuff came and it came into the places that we lived in. And some of us made decisions that we felt were best to survive.”

Some of the older kids and fathers started disappearing. They were recruited by gangs, lost to violence, addiction or life in prison. And even young kids like Tyson experienced traumas that would change them forever.

He tells me about one of them: “I had a friend, I'm 10 years old.”

The friend was 10 years old too. One night he started drinking with his older siblings and ended up dead.

“That hit me, bro,” he says. “I'm a kid. You feel me? The end of this person has just happened. I didn't understand that. And I remember that vividly is a moment where whatever I thought was my childhood, that ending, and then having to step into a deeper understanding of the world and the consequences of decisions, and all of that.”

Tyson remembers this as the first moment when he started to ask the bigger questions. Religious understanding, higher power, heaven, hell conversation, what's going to happen after this life.

Not long afterwards Tyson’s parents decided to sell their home in the Storybook neighborhood and moved across town to a two story home in a cul de-sac. His parents still live there.

The Black room

Walking through the foyer I immediately notice a theme of African cultural artifacts. Tribal masks and woven farmer hats with intricate patterns hanging on the wall.

His mom tells, “Here in San Jose, it's not that many African-American people. And the few that we knew, we all felt the same way. Like our kids aren't getting their information. So we would have Sunday classes and we would have lessons. We take them on field trips. And that's how they got to understand who they were as people.”

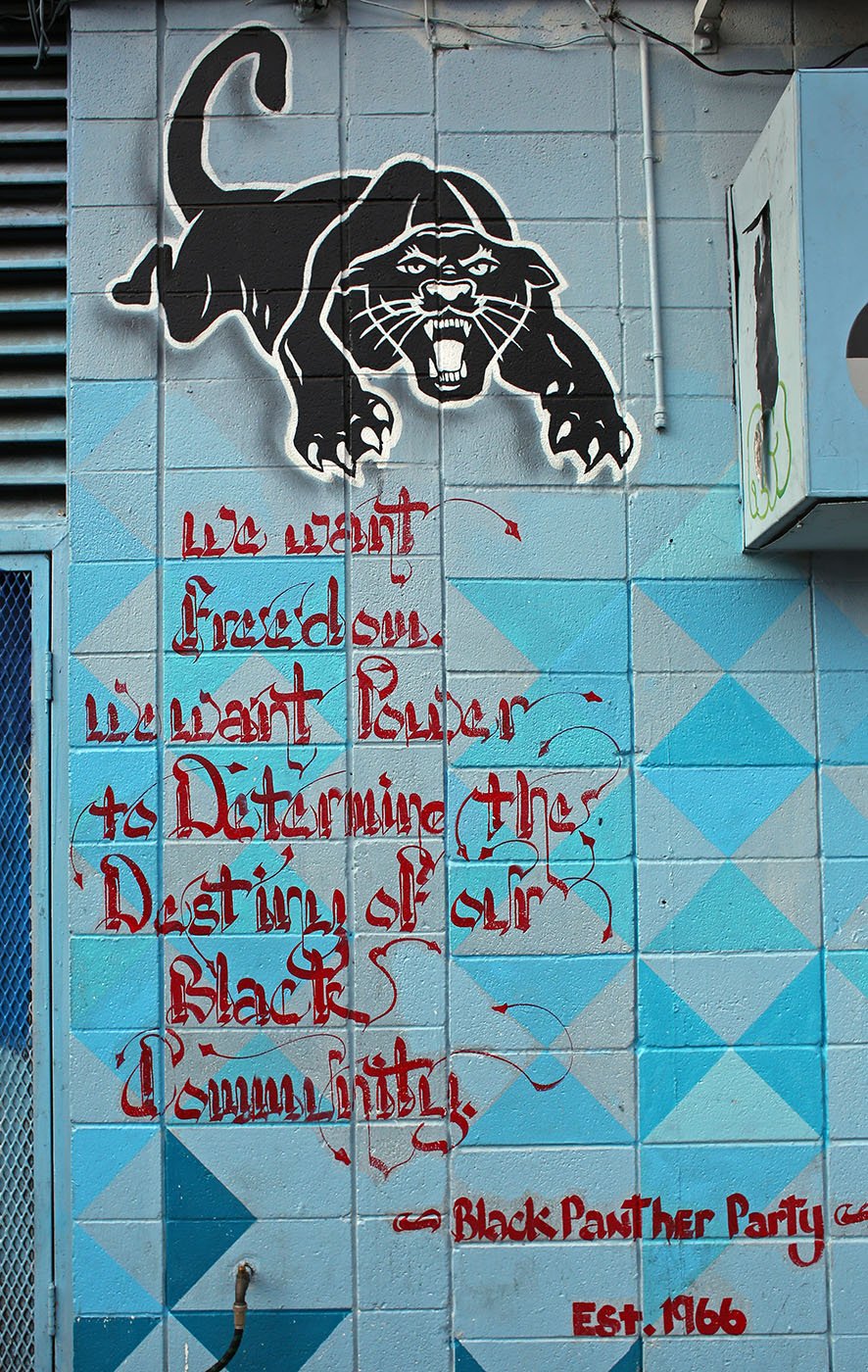

We sit at the kitchen table, and talk about her upbringing in the South, how she came to Oakland and met her husband. He was a member of the Black Panther Party, the famous group founded there in response to police violence in 1966. She volunteered for their free breakfast program, feeding kids in black neighborhoods before school.

Her stories reminded me of something Tyson had mentioned about the house. A special room called The Black Room.

She asks Tyson, “You want to take him to the black room?”

Tyson takes me upstairs.

When they moved into the house, they had this extra bedroom. Tyson’s parents filled it with posters of black icons. Angela Davis, Malcolm X, Muhammad Ali, A picture of the famous 1968 Olympics black power salute. For Tyson, this room, similar to the book about his enslaved ancestors, had a huge impact.

“I'm seeing history and people in revolutionary struggles from all over the world in my very home,” he says.

It’s also where his journey to Islam began. He became fascinated by the life of Malcolm X.

“I decided I wanted to follow the path of Malcolm very, very early on,” Tyson says.

“So whatever I can learn about his path, what helped build him, became part of me. I remember deciding, probably like around the age of 10 or 11, I'm like, ‘Oh, Malcolm was in the nation of Islam. I know in the Nation. They don't eat pork. I won't eat any more pork.’ Simple as that.”

His mother remembers how intense he was even at that age. She remembers one time they were at a sports banquet.

“He was getting this award, um, before we got ready to eat. You know, the pastor wanted to do the blessing and everybody bows their heads. But my son... “

She cups her hands to simulate the way Muslims pray.

“I told my husband, oh look, there's our little Muslim. And I said, that's who he is.”

“So in my young mind, the most powerful image or representation that I saw of blackness and an unapologetic revolutionary approach was that of Malcolm,” Tyson says. “Malcolm was amazing and still is to this day. And so the calculus in my mind was whatever produced him, I need to be connected to.”

And that included Malcolm’s faith.

Still, it would be years before Tyson took his Shahada and officially became Muslim. I asked about that moment many times. And every time I asked, Tyson deflected. It was clear he was trying to steer me away from telling his story that way.

His conversion didn’t come from a period of spiritual searching - the way it does for many converts. From the beginning this was about joining the ranks of black Muslim freedom fighters that came before him.

Tyson wanted me to understand that his conversion wasn’t about soul-searching. It was about placing himself in the struggle.

Your spirituality can be part of your political activism. They're not, they don't have to be separate boxes. It's like, all right, almost step into my political activist, organizing revolutionary box, and that means I'm not in my spiritual box anymore. It's not that. So in what I have experienced as part of the black experience, the spiritual, the political, the revolutionary, the artistic, the creative. It's all intertwined.

When Tyson went to college at San Jose State University, he started writing poetry and rapping. He’d always been quiet and introverted but on the mic he let out a huge personality.

He started meeting other Muslims at the mosque and at cultural events. There was a burgeoning scene of Muslim hip hop artists in the Bay Area at the time. And they were determined to not rely on the commercial music industry for their success. Tyson joined forces with a DJ and another rapper to form a group called 11:59. Their lyrics reflected a strong sense of Islamic spirituality while being true to their own experiences as Black Americans.

“We just passing through / Life is but a test / Come on let’s get free y’all / Die before your death”

The group traveled around the United States and to Muslim lands abroad. Tyson’s travels broadened his understanding of the world and his faith, as he met all kinds of people that claim a relationship to Islam.

“We thought that with this is this unifying tool of Islam that people would be able to see beyond some of the things that colonization, imperialism, just the global system of racism have thrown into each of us, regardless of where we are in the planet, he says.”

He and his band mates felt that the Black American struggle held lessons for Muslims all over the world.

They toured for years. But eventually, the band dissolved. And Tyson’s focus turned back home. His relationship to religion shifted. He became less concerned with connecting with Muslims abroad and more attuned to the struggle that brought him into the faith to begin with.

A visit to Panther territory

In February 2020, just a month before things closed down because of the coronavirus pandemic. Tyson and I driving around West Oakland, visiting old Black Panther landmarks in Oakland.

He asks me, “Have you been to West Oakland like this?”

I tell him, not with a tour guide.

“I don't know if I'm a tour guide, but I'll point out a few things,” he tells me.

“So right now, we're at 14th and Peralta. So West Oakland is the official home of the Black Panther party.”

I had passed these streets countless times but hadn’t known the history. I began to sense the enormity of the struggle that weighs on Tyson. 50 years ago, young black people organized on these streets to stand up to police brutality.

What we driving through. These are the streets that those brothers and sisters were on. This is where they was pulling their first recruits, and this is what produced that which produced a movement that had an impact all throughout the United States and beyond. That's powerful man.

Teaching as revolution

These days, Tyson spends his time trying to live up to this history. He’s writing, teaching, and organizing in the black community. In a classroom where he’s teaching, the desks are arranged in a circle. The students watch him intensely.

“We're going to break it down,” he tells them. So we gonna take this line by line. Y'all good. Y'all ready? So this is Between Huey and Malcolm.”

Tyson starts to read one of his poems.

“The doctor Huey P Newton had an epiphany once. And then he said, I don't expect the white media to create positive black male images. So he wouldn't be surprised to see how evening networks accumulate their net worth of billions off assassinating the character of our children.”

It’s from a book he published called Black Boy Poems. He uses it in a curriculum he’s developed. It’s designed to teach black students the revolutionary history of the 1960’s.

“Ain't no revolutionary curriculum that people are being exposed to that is put out by the state of California or any other state that we're talking about,” says Tyson. “They're not doing it and not going to give you information that's going to lead you to fighting for your freedom and liberation.”

He wants the students to see themselves in that history, the way the green book about his ancestors and the black room in his house did for him as a kid. This is how Tyson described himself in our first interview. I had asked him to tell me his name and what he does.

“Some people call me an author. Some people call me an emcee,” he said. “Some people call me a poet. Some people call me educator and activist and organizer, so many different things. Freedom fighter is first. “

He was raised seeing himself as part of the continuation of the struggle. The struggle began with the ancestors of his ancestors, who were brought in bondage and forced to labor on these lands. They lost their languages. Their traditions. And of course their religious knowledge.

Everything Tyson does today is about his connection to this community. To his forebears. To fallen leaders. It’s what informs his music. His writing. His teaching. It’s why today, if he’s not working, he’s volunteering and organizing.

This is what Tyson wants me to understand. that his choice to be Muslim is at the heart of his revolutionary stand against a history of oppression.

“I want to live a life that's principled that reflects the conditions that we're in,” he says. “And being true to those principles. And having a purpose in the way that I live my life and serving the people in the community that I come from. And standing up for the things that need to be addressed in this moment in time because that's what my ancestors did before me.

Tyson continues. “I'm going to honor them and I'm going to carry that on because it's the right thing to do. If you put all those pieces together, that's what's at the heart of what I stand on in terms of faith and spirituality and practice.”

***

Imran Ali Malik is a freelance writer and audio producer, currently pursuing a master’s at Berkeley Journalism. He is the producer of the Submitter podcast.

The Spiritual Edge is a project of KALW Public Radio. Funding for Becoming Muslim comes from the Templeton Religion Trust.