Created in prison: a new way of thinking about evolution and spirituality

For inmate Gary Shepherd, a new kind of spiritual wisdom emerged once he started to study evolution. It’s made him what he calls an “evolutionary.”

By Mark Betancourt

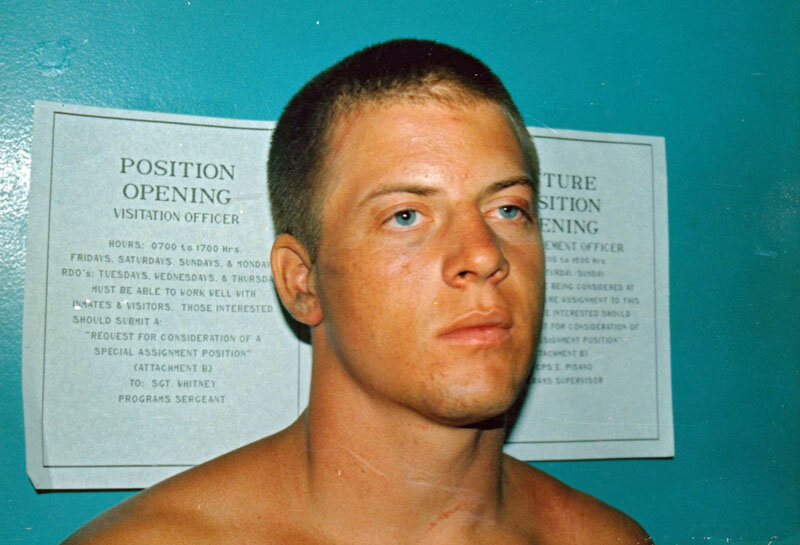

JUNE 12, 2017—Gary Shepherd has spent more than half of his 45 years incarcerated — his entire adult life. In that time he’s become a self-taught scholar and a self-described spirit warrior, putting into action a deeply-held belief in the power of altruism and cooperation. All of this springs from Shepherd’s study of evolution. It’s made him what he calls an “evolutionary.”

“It doesn’t mean just evolution,” Shepherd says of the term. “It means revolutionary, because there’s a spirit of action and there’s change.”

Shepherd is incarcerated in the East Unit at the Arizona State Prison Complex in Florence. Through years of good behavior, he’s worked his way up to the honor dorms, the coveted place to live in East Unit. In the center of the yard, surrounded by what look like army barracks, is a cluster of double wide trailers lined up end to end. There Shepherd has his own room and a door he can close and open whenever he wants. But it’s still prison: the yard is surrounded by two layers of chain link fence, both topped by concertina wire.

The Road to East Unit

Shepherd had been a heavy drug user as a teenager, and he was no stranger to the law. But his real trouble didn’t begin until 1991, when he was 20 years old. He’d done a little time for burglary and he was on parole, which he promptly violated. When his parole officers tried to arrest him at a mall in Tucson, he fired a gun into the ground to create a distraction. At the time, the offense carried a mandatory sentence of life in prison.

“[It’s] so much time when I didn’t hurt anybody, nor did I intend to hurt anybody,” Shepherd says. “To me, that seemed instinctively very wrong.”

After only a month in prison, Shepherd tried to escape, assaulting two guards in the process. That earned him a year in solitary confinement — inmates call it the hole.

“I would just walk back and forth and just think, ‘What happened in my life? What really went wrong? What’s wrong with the system?’” he remembers. “It just seemed so bizarre to me. It seemed like the problem was much bigger even than me.”

Figuring out this problem, despite its immensity, became Shepherd’s lifeline. He started reading voraciously, trying to make sense of everything that had happened to him. He wasn’t studying case law or learning a vocation like many prisoners do. Instead, he devoured books on anthropology, history, biology, philosophy. He was trying to understand how the whole world works.

Then from an unexpected source, came an epiphany. Watching TV one day, Shepherd saw a PBS special on early hominids and how they evolved into modern humans.

“It completely changed me,” he says. “It’s almost like a light went on and I felt like that’s absolutely where we came from, and it was a fact. And it was very quickly that I foresaw the purpose of life. It almost gave me like a faith.”

A spiritual scavenger

Shepherd’s parents weren’t religious, and he says he didn’t have much of a moral framework growing up. Since he’s been in prison though, he’s become a spiritual scavenger, gathering concepts and practices that can help him survive.

Early on in his sentence, in solitary, a Sikh chaplain taught Shepherd the basics of meditation: how to control his breathing and clear his mind. Later, that led him to look into other mindfulness practices. He started learning yoga and tai chi from books and mail-order DVDs. He read books on Eastern philosophy.

He says Sun Tzu’s “The Art of War” is his favorite, because it provides practical advice on how to survive in a violent situation — for example, everyday life in prison.

“It’s not like most people think,” Shepherd says. “They hear that word ‘war’ so they automatically think violence. [The idea is actually] to do the most with the least, to resolve problems before they occur, and ultimately to try to make conflict altogether unnecessary.”

Shepherd hasn’t always been so cool and collected. His nickname in prison is Scrappy, and not for nothing. When he first got to prison, he fought anyone who interfered with him, even guards. But as his worldview began to shift, Shepherd used this reputation — and the concepts he was learning — to take on a kind of philosophical crusade.

A reading list handwritten by Gary Shepherd. PHOTO CREDIT: Gary Shepherd

If he saw a potentially violent situation unfolding, he’d intervene, often putting his life at risk to confront fellow inmates who were on the verge of hurting or killing someone else.

“In a very respectful way, I would let them know that that wasn’t going to happen,” he says. “And that it wouldn’t be allowed to happen without there being a response.”

Shepherd also started debating his fellow inmates about things like the origin of life — challenging their beliefs, or in some cases introducing them to the idea of evolution for the first time. Surprisingly, people were interested, even seeking him out to hear what he had to say.

“It almost [made] me an authority figure on certain things,” he says. “They looked to me almost like a leading personality because of my knowledge.”

Wading into an evolutionary debate

The concept he tried hardest to impress on his fellow inmates was something called “group selection,” a subcategory of natural selection. This is where Shepherd is wading into a somewhat controversial scientific debate.

The traditional view is that evolution depends on the strength or intelligence of individual animals, and that competition between those individuals is the main driver of natural selection. But some scientists theorize that cooperation is equally, or even more important than competition, and that natural selection happens at the group, as well as the individual level. For humans, that means groups of people who work together can survive to procreate — those who fight amongst themselves eventually die out. Groups that cooperate with other groups fare even better.

As crazy as it sounds, Shepherd says he would pitch this idea to the gang leaders in prison, in an effort to get them to be more community-minded.

These conversations weren’t just about convincing his fellow inmates to be more peaceful, they came from a deep-seeded belief Shepherd holds about the nature of evolution. In his studies, he had come across the writings of Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, a 20th-century Jesuit priest who theorized that evolution is a conscious process, that the universe wants to perfect itself, and that humans can actively participate through the choices we make. It was, and still is, a fringe concept in the mainstream science world, but it fit perfectly with Shepherd’s image of himself as an evolutionary spirit warrior.

“I’m filled with this sense of injustice, and unfairness, and I didn’t like to see prisoners mistreated by other prisoners or getting hurt, when I feel like we should be focusing on working together more as a team,” he says.

Altruism is what Shepherd really found in the science — a sense that we have to take care of each other in order to succeed as a group, whether it’s a small group of prison inmates or the whole species. And that’s what he means when he says that evolution gave him a sense of purpose.

By way of explanation, he quotes Matthew 6:33: Seek ye first the kingdom of God… and all these things shall be added unto you.

Spreading the word

Over time, Shepherd found more ways to live out this sense of purpose that he’d found. Around 2003, 12 years into his sentence, he got together with a couple of other inmates and started a peer education program they called “B-Free.” They would teach basic skills in the prison, health and hygiene, and tips for survival after release. The prison gave them an office to work out of, and a little bit of pay, about $3 a day.

Shepherd also saw the classes as an opportunity to educate fellow prisoners on his developing blend of science and philosophy.

“We would start with the Big Bang,” he says. “We’d go through quantum realms. I’ll talk about what creates cultural evolution, I’ll get into the evolution of our morals, multi-level selection.”

Shepherd was also sharing his own special blend of yoga and mindfulness practices, including something he calls “poet-chi.” It’s basically the tai chi he learned, but he adds stream-of-consciousness ruminations on evolution and spirituality to go along with the movements.

Colleen Fitzpatrick-Rogers worked as a substance abuse counselor in the state prison complex in Florence. She’s retired now, but she knew the guys running the B-Free program, and she would help them get materials or information they needed for their classes. She also invited Shepherd to teach yoga and mindfulness to her addiction groups.

“When I brought somebody like Gary Shepherd in front of my class, and he spoke to these inmates, they listened,” she says. “It was new to them. You don’t have some guy talking to you and doing yoga and teaching you in a crack house.”

Fitzpatrick-Rogers says that Shepherd commanded respect from other inmates partly because he lived by his philosophy. He practiced what he preached. And also because doing so had so clearly changed his life.

“He just found what he needs, as far as peace inside of him,” she says. “And not many people — outside even — ever get that.

“The Work”

Troy Froehlich was profoundly influenced by Shepherd’s ideas, and his friendship. He worked with Shepherd on the B-Free program until he was released in 2014, having served a total of 24 years for bank robbery and assaulting guards in jail. He says the things he learned from Shepherd helped him find inner peace, too.

The manual—a guide to life on the outside—that Gary made for Troy Froehlich before his release from prison.

“Whenever it looks like it may be a stressful situation, or something that could raise an anxiety in me,” says Froehlich, “I just realize that I’m a part of evolution, that this is the way it’s supposed to be. I look around and I think, ‘Wow, this is wonderful.’”

Froehlich lives in Tucson now, just an hour and a half down the road from the prison where he met Shepherd, who he calls his best friend. He’s been fixing up his little rental house, which he shares with a shy black mutt he rescued from the street. He named her Scrappy, after Shepherd.

Like Shepherd, Froehlich experienced an awakening in solitary, after which he started studying history, psychology, religion, and melding it all into something that worked for him. He gravitated toward Joseph Campbell’s comparative mythology, and started observing the Jewish Sabbath as a mindfulness practice. When he met Shepherd one day in the chow hall, they instantly recognized each other as kindred spirits. For the next ten years the two collaborated every day on what they call “the work.”

“As soon as he would come up with a concept, he would come down to my room immediately and start sharing it with me,” says Froehlich. “We would walk laps on the yard, discussing evolutionary possibilities.”

Shepherd says that he and Froehlich clicked because they shared an extreme form of altruism, both willing to risk their own safety to prevent violence in the prison, and to stand behind the concepts of cooperation and fairness they believed in so fervently.

“We became like one unit,” Shepherd says. “If you dealt with either one of us you’d have to deal with us both as one. And I would lay down my life for him and he’d lay down his life for me.”

Froehlich was granted parole. Shepherd helped him with his speech for the parole board and before he left, Shepherd made him a handwritten manual on how to function in the outside world. It was based on everything they’d learned and taught to other inmates for ten years. The manual was the only possession Froehlich took with him.

“I didn’t tell Gary this,” says Froehlich, “but when I got into the staff vehicle at the prison, you know, four o’clock in the morning — I’m just sitting there and a tear rolled out of my eye.”

He says that even though he had his own epiphany before meeting Shepherd, it’s really Shepherd’s influence that turned his life around.

“It is entirely possible that without slowing down my brain and starting to accept these concepts that we talk about and knowing that there’s a different way,” he says, “I may have just continued on the life that I was living before, which led me to bank robbery. Why would I change?”

Widening the circle

These days, Shepherd’s community is expanding beyond those he’s met in prison. Last year, with help from Fitzpatrick-Rogers, he reached out to David Sloan Wilson, a professor of evolutionary biology in Binghamton, New York. Wilson is a central player in the evolutionary altruism field, and Shepherd had read his book “The Neighborhood Project,” which argues that people can improve their communities by using evolutionary theory as a guide for cooperative behavior.

“By the first letter, or exchange of a few letters, it was clear that in some ways, what we were doing was quite similar,” says Wilson.

The two men struck up a kind of academic friendship, talking on the phone every week. Wilson even recorded one of their conversations and published the transcript in his online evolution magazine, This View of Life.

In the meantime, he was sending Shepherd more books, becoming Shepherd’s evolutionary mentor.

“I’m his instructor in a sense, if he was a college student,” says Wilson. “But of course, he’s much more voracious and passionate than almost any of my actual students.”

Wilson doesn’t quite agree with some of Shepherd’s ideas, like the one about a ubiquitous force that’s deliberately trying to improve itself through evolution.

“Gary has been influenced by lots of trends, including Eastern religious and spiritual traditions,” says Wilson. “It’s just part of human nature to hold beliefs that are false in the scientific sense of the word, and the reason that we do is that those beliefs are useful. Those are the beliefs that help us get by.”

As for Shepherd’s belief that we have the ability, even the obligation, to help evolution along — Wilson says that’s not so far-fetched.

“The reason that science often doesn’t function in the same capacity as a religion is that it merely tells you what is. It doesn’t tell you what to do,” he says. “It’s up to academic science actually, to catch up to Gary in an interesting way, as to is there some sense in which a person, or people, or all of us as a society, can be agents of evolution.”

I asked Wilson whether Shepherd’s journey is itself an example of cultural evolution — a whole school of thought developed in an isolated environment, like an academic Galapagos Island.

“Most novelties arise in isolated populations,” he answered. “That’s where new things happen. [Shepherd has] come up with something that hangs together for himself. Then of course, whether it spreads and survives in other contexts remains to be seen.”

Shepherd’s whole goal in life now is for his ideas to spread and survive.

He says that if he’s ever able to get out of prison, he’ll link up with Froehlich and continue with “the work.” He’s thought about starting a business creating internet courses that explain in simple terms, the ideas they’ve spent all these years developing.

Shepherd is also working with a lawyer from the Arizona Justice Project to see if his sentence could be appealed. The law that mandated his life sentence was changed shortly after he went to prison, and that may provide a way for him to get out sooner. If that doesn’t happen, Shepherd’s first chance for parole isn’t until 2028.

Because he can’t control when or whether he gets out, Shepherd doesn’t think about it too much. But he does look forward to joining a community on the outside that shares his beliefs, and his sense of purpose.

“I can find people like David to be around, and these other people that I consider to be the most intelligent and altruistic people in the world, that are a force for positive change,” he says. “And I want to help them and make sure they’re secure, and their families are secure, and that we can do all that we can to make them successful. And I want to barbecue and eat with them. I just want to be part of that whole family, you know?”

I asked Shepherd whether, given the unfairness he saw in his sentencing, he regrets ending up in prison. He answered, without hesitation, “No.”

“I’m glad that it happened to me,” he explains. “Because I wouldn’t be who I am without the experience. But more importantly, I have found what I believe to be the truth of where we came from, and why we’re here, and what we need to do in the future. And the feeling of fighting for that and contributing to that, I wouldn’t trade it for anything. Everything that happened to me was worth it.”

* * *

The Spiritual Edge is a project of KALW Public Radio. Funding comes from the Templeton Religion Trust.