Zohar translation revives poetry and nuance of Jewish mystical text

The sensual, enigmatic language of the Zohar is brought to life in a new translation.

By Judy Silber

SEPT 19, 2017—Western literature’s most important books have been translated, not once, but many times. The book at the top of the charts is the Bible: more than 100 translations, and that’s just in English.

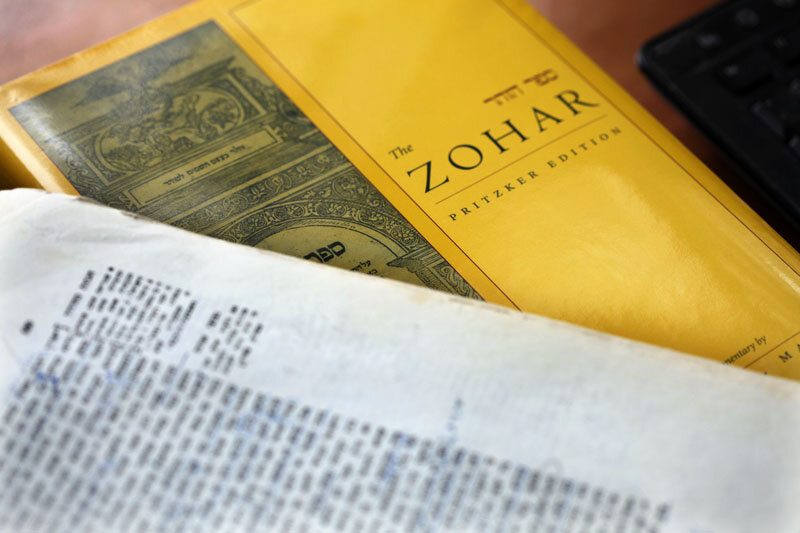

Why so many? It’s hard to capture all the nuances of meaning and style from the original. Which is why a recently completed translation of the Zohar—the book at the bedrock of the Jewish mystical tradition of Kabbalah—is so important. Scholars say its poetic interpretation captures the original 13th century prose. Berkeley scholar Daniel Matt spent almost two decades doing the translation and writing commentary that goes with it. That’s a long time, but the Zohar is a massive book. When complete, the new work will total 12 volumes, each hundreds of pages long. Matt is responsible for most of it.

Scholars and rabbis alike say the new work could help revive the Zohar’s place in Jewish life. For centuries, the Zohar’s mystical teachings held a central place in mainstream Judaism. It was a guidebook to a closer relationship with the divine, for connecting to something larger than our small human selves. Its teachings were considered powerful and sometimes dangerous. Because of this, it’s been said that at one point Kabbalists advised that only learned, married men over the age of 40 should study it.

The Zohar is central to the Chasidic branch of ultra-orthodox Judaism. Madonna also brought fame to the Kabbalah Center in Los Angeles. But for the most part, the Zohar’s teachings are unknown. One reason is the Zohar simply dropped out of style. But for a long time, there was also no good English translation. Basically, if you wanted to study Zohar, you had to know Aramaic.

Rabbi Aubrey Glazer is an early adopter of Daniel Matt’s new translation. Already, he’s brought it to the attention of his synagogue, Congregation Beth Sholom in San Francisco.

“So the Zohar is probably one of the most magical and intricate books on the Jewish bookshelf,” said Glazer. “But also on the bookshelf of spiritual seekers at large.”

Every Saturday, Glazer holds Zohar study sessions—which are really more like meditations. Each week he reads a passage from Matt’s translation, which has been released volume by volume since 2004. He tells congregants not to try and understand everything, but to listen and be open to whatever images come up.

“At the head of potency of the king, he engraved engravings in luster on high. A spark of impenetrable darkness flashed within the concealed of the concealed, from the head of infinity. From the head of infinity, a cluster of vapor forming in formlessness. Thrust in a ring, not white, not black, not red, not green. No color at all.”

The Zohar is a provocative book that addresses fundamental questions of existence. Glazer says the new translation makes its ideas accessible to an English speaking audience.

“How people imagine the Big Bang occurred,” explains Glazer. “What was it like at that moment just before, or the millisecond before creation and the world came into being from the place of dark matter and the place of the cosmos kind of birthing itself into being? That’s part of what the Zohar in its own unique way is trying to capture.”

The writing is highly enigmatic, and the Zohar’s answers are often less literal than visceral. Glazer says it’s like jazz. Maybe you don’t know where you’re going, but you can get lost in ethereal worlds that grab hold of imagination and heart. And some of the Zohar’s ideas are pretty radical. How is God described? Forget the old man in the sky. The Kabbalist God includes male and female traits. The Zohar also describes God as being beyond gender, as infinite. Boundless. What’s called the Ein Sof.

“So as to why it’s reemerging now, it’s a great question,” muses Glazer. “And to me, it seems like it’s part of the Zeitgeist. The Jewish world has been moving in the direction of—perhaps more oscillating—between an embrace and a repression of the mystical.”

In the mid-1800s, mainstream Judaism began to reject the Zohar’s teachings as superstition and veer more towards the rational and intellectual. That continued as Jews immigrated to the United States during the late 19th and first half of the 20th centuries. But then came the 1960’s and 70’s, when the teachings of Buddhism and Hinduism arrived in the West, bringing spirituality more into vogue. Separately, Jewish scholarship on the Zohar began to appear. Jews began to realize they had their own rich, mystical tradition to call on.

“It’s something that now is re-emerging with great force and bravado and thanks in no small part to the remarkable, remarkable work of Danny Matt in Berkeley,” said Glazer.

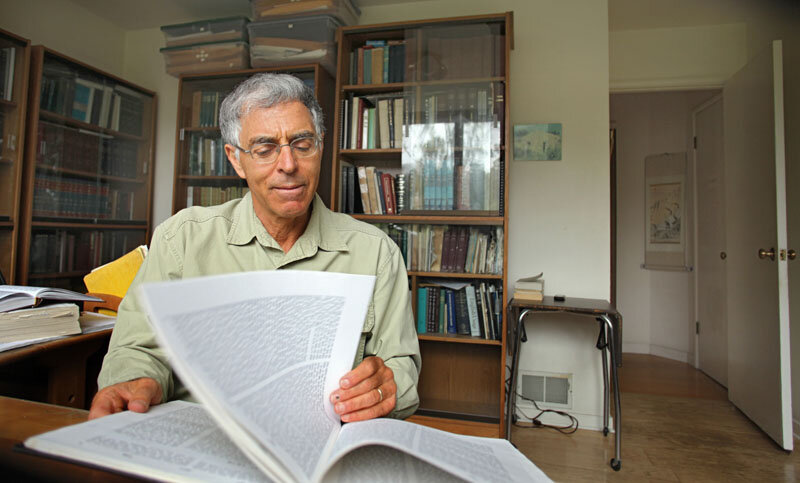

Daniel Matt says he had no intention of doing the full translation. He fell in love with the Zohar as a young man in college. He wrote a few books about it. And back in the early 1980’s, as a young professor at the Graduate Theological Union in Berkeley, he finished translating what he says was about two percent.

“And ever since then, people said to me, well when are you going to do the other 98%,” Matt said. “And I would say, well I don’t want to spend the rest of my life translating the Zohar.”

Then a friend, a famous Zohar scholar, called in 1995. He said a rich Chicago family, the Pritzkers, who owned the Hyatt Hotels, wanted to fund a full translation. Matt’s first impulse was no. He thought: it would just be too hard.

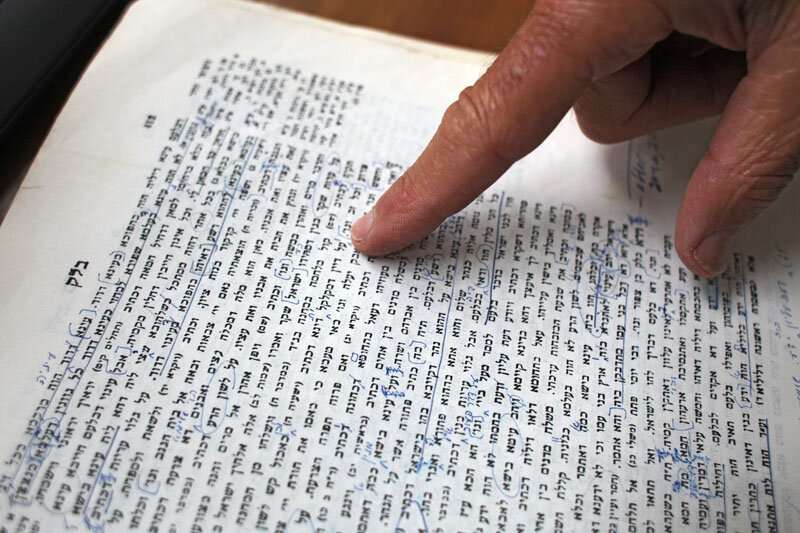

That’s because as a translation project, the Zohar has unique challenges. Its origins go back to 13th-century Spain when a man named Moses de León claimed to have discovered a bunch of ancient manuscripts. Today, scholars believe de León himself was the primary author. Their evidence is the Zohar’s unique style. It includes smatterings of Hebrew and Spanish words. And it’s written in a strange Aramaic, with made up words.

But it wasn’t just the bookish part that made Matt nervous. There were also the spiritual demands.

“There are intellectual tools you need. You have to use dictionaries. You have to look up passages in the Bible,” said Matt.

“But to make sense of the Zohar, you’re really exploring your own mental and spiritual world. And that’s really why the Zohar’s so challenging. You’re not just studying what’s out there on the page. You’re really constantly testing it and trying it out within.”

Matt felt like he just wasn’t up to it. But then that call came and he agreed to meet with Margo Pritzker. She had been studying the Zohar with a rabbi. They were using an older English translation, what’s known as the Tsinsino translation, which was done in the 1930s. It was known to be incomplete. It skipped over difficult passages and words, and also erotic passages that served as metaphors for the book’s mystical contents. It also had no commentary, no explanation of the Zohar’s abundant, but obscure metaphors.

Unhappy with what they had to work with, “One of them said to the other, let’s do a new translation,” said Matt.

Matt said he agreed to meet with Margo Pritzker, but had already decided ahead of time to try and talk her out of it.

“And I gave my reasons, why it was so impenetrable and challenging, but at one point Margo Pritzker said, look I understand your hesitation, but if you did do it, how long would it take?”

Twelve to fifteen years, Matt answered.

“I mean, I was just trying to be honest, but realizing in my mind, that was, you know, interminable,” he said. “And Margo said to me, you’re not scaring me. And somehow when she said that, something clicked inside of me, maybe it was almost a dare. She was saying, I’m not scared, how come you’re scared?”

Daniel Matt retrieves a well-kept cardboard box from a bookcase in his study. Inside, carefully wrapped in tissue paper, is a thick book bound in royal red. It’s a gift from Margo Pritzer, from after he finished his ninth and final volume a few months ago. With reverence, he runs his fingers over the still dark, black ink.

“It was published in Italy in 1558,” Matt told me. “There were actually two competing publishers that put it out within the same year or two in two Italian cities in Crimona and Mantua. And this is really one of the rarest Jewish books in the world.”

Matt points to the 450-year old cover of his first edition copy. On the title page is a drawing of an intricately drawn gate.

“It’s called in Hebrew, the sha’ar, the gateway,” Matt said. “And it’s actually an image of a gate, opening the Zohar, making it available to the world, printing it for the first time.”

Matt’s new translation and commentary promise to once again make the Zohar more accessible. It may never be as popular as the Torah, Judaism’s most revered book. But the stories and teachings are beginning to reach a larger Jewish community. Matt’s lyrical interpretation makes the exploration possible. Two friends strolling through Palestine’s Galilee region. Bumping into strange and mythical characters. A donkey driver. A beggar. A child. Along the way, the friends discuss the Torah line by line, and offer novel, mystical explanations.

“The Zohar is taking the foundational text of all Western religion, taking the Bible and turning it into a mystical text,” said Matt. “You know, transforming the meaning, line by line and verse by verse. So it enables you to be part of Western religion and yet experience this radical, mystical rebirth.”

The Zohar’s paradox is that it conveys an experience beyond language, through words. You read it. You study it. And those who know it say its wisdom slowly trickles in.

Matt tells me there’s a passage in the Zohar that turns the story of the Garden of Eden inside out. In the bible, God expels Adam from the garden. But the Zohar says, who kicked whom out?

“Did God kick Adam out or…?” Matt asks. “And the Zohar does something very beautiful here. It says, or not? And as you’re reading it, you can’t help but think, wait a minute, the alternative is that Adam kicked God out? We kicked God out?

That’s what the Zohar’s teaching, he said. That we’ve lost touch with the original oneness, and that’s what it means to be expelled from the Garden. But he says the Zohar teaches there’s a way to recover that knowledge.

“There’s a way to find our way back to that harmony through love, through spiritual awareness, through quieting down the busy mind,” Matt said. “And the Zohar enables you, or challenges you to do that.”

Scholars say it will likely take many more books to recognize all the messages encoded by the Zohar. But eight hundred years after it was written, Daniel Matt’s translation makes that possible.

* * *

The Spiritual Edge is a project if KALW Public Radio. Funding comes from the Templeton Religion Trust.