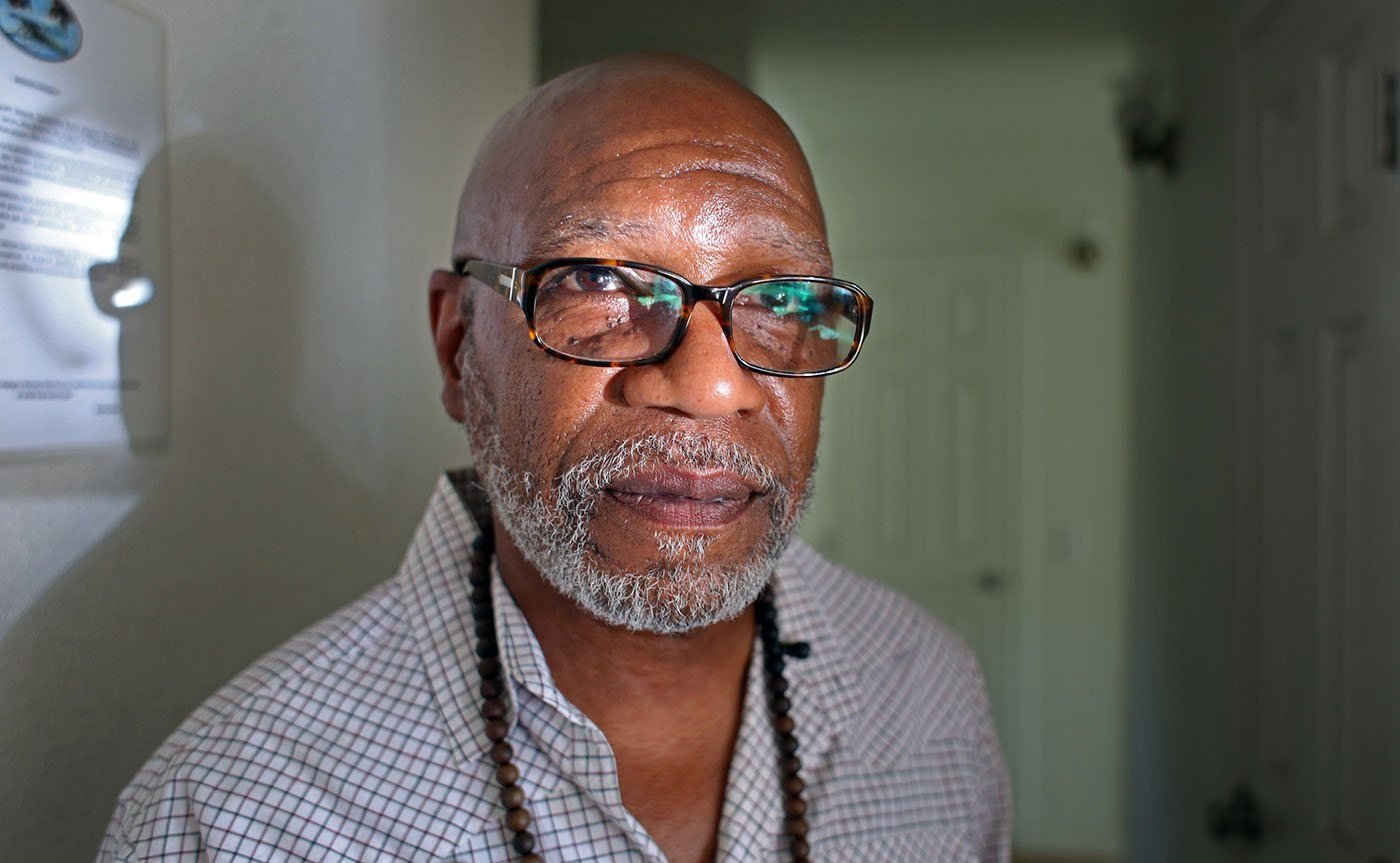

Becoming Muslim: WENDELL

Finding freedom in prison

Listen and subscribe to The Spiritual Edge wherever you listen to podcasts - Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Google Podcasts.

By Hana Baba

"Malcolm X said it himself. He said there is no audience that is more primed to hear the message of Islam than the black man in prison."

An important part of the Black Muslim story in America has to do with incarceration.

Scholar SpearIt is a professor at Thurgood Marshall School of Law at Texas Southern University and author of “American Prisons: A Critical Primer on Culture and Conversion to Islam.”

“Starting in the 1970s, we started on this turn to mass incarceration. And so the sitting demographic of people was large groups of African American men. And so they are literally a captive audience for the message,” SpearIt says.

Thirty to forty thousand prison inmates convert to Islam every year, according to SpearIt. He argues that the Black Muslim story can’t be told without looking at what’s happened in American prisons.

Harlem of the West

Wendell El-Amin James grew up in San Francisco during the 1960s. It was a time of cultural revolution and radical ideas. For the city’s Black communities it was also a time when the jazz scene flourished in the Fillmore district, known as the Harlem of the West.

As a kid of just 11 or 12, Wendell James saw a lot on the city’s streets —pimps, drugs, clubs. Wendell didn’t learn how to read. He was classified as special ed for a speech impediment. As a teen, he would hang out in the neighborhood. He’d be in the city on Saturdays and church on Sundays. And then there was an unexpected turn of events. His girlfriend got pregnant. He got married at age 18.

“My mom wasn't going for that,” Wendell says. “She said, ‘You be responsible. You get a job and you make sure this girl is taken care of.’ I got me a job in a shipyard at a young age. But then I became part of the street as well. And I had friends that were selling marijuana, weed.”

He started dealing. He needed money to keep a house and support his new family. Weed led him to cocaine and heroin.

“I became a dope dealer in San Francisco,” Wendell says.

This was also a time of activism and social change. It was the height of the free speech movement in Berkeley. The Black Panthers were in Oakland. Plus, the Nation of Islam had a strong presence in the lives of Black people in the Bay Area. Wendell’s older brother was a member.

“I used to go to the temple with him,” Wendell says. “And I used to like it because they marched in the drills and it was structured. You know, I liked that. I loved it!”

Wendell admired the Nation, but he was still young and he had the responsibility to care for a family before the age of 20.

He dealt drugs for years. The money was rolling in. But by the late 1970s, he wasn’t just dealing heroin and cocaine, he was also using.

He and his wife were addicts. One day he was in San Jose and was arrested. He ended up serving six months in the county jail.

That was Wendell’s first involvement with incarceration. After he left jail, he went back to his old drug life on the outside. It was the same for a lot of people. At the time, recidivism rates were notoriously high.

In 1987, he was charged with another crime — a much more serious crime: first-degree murder.

“I was scared to death.”

Going to prison

Wendell maintains his innocence to this day. But he was convicted and sent to prison for 27 years.

While awaiting his sentence in county jail, the men inside with him gave him a reality check about what would come next.

“I went into a holding tank with people that were older than I was,” he says. “Old Gs, so to speak. And he was telling me, ‘Youngster, you goin’ into prison. You charged with murder. You're going to prison man.’”

“A lot of Old G's had been to prison and at that time it was a war going on in prison,” Wendell says. “You know, Blacks and whites and Mexicans. People were dying every day. So they said, ‘You going to old Folsom.’ And that's where it's really bad. I said, ‘Whoa.’”

This was the height of Ronald Reagan’s War on Drugs in the 1980s that led to prison populations swelling. A 1985 report on violence at Folsom State prison counted 120 stabbings in just six months that year. A prison guard was killed the same year Wendell was going in. So the older men Wendell was getting advice from had a big tip for him.

They told him that when he got to prison he should find the Muslims.

Wendell recalls that conversation. “‘They said, ‘You hang out with the Muslims, you’ll be okay.’ I said, ’What do you mean by that?’”

“He said, ‘Nothing will happen to the Muslims.’’

“‘What you mean about that?’”

“He said, ‘Muslims don't play. So you hang out with the Muslims, you'll be straight.’”

The Muslims. Like his brother back in the 60s. However between that time and now, much had changed with Black Muslims. That change included charismatic leader Malcolm X.

Malcolm X was assassinated after splitting from the Nation of Islam. Its leader Elijah Muhammad died in 1975 and his son Warith Deen took over, moving the movement towards mainstream Sunni Islam.

By the time Wendell went to prison in the late 1980s there were a number of different Black Muslim groups on the inside, and they were all reaching out to incarcerated men more than ever.

“The Muslim groups are the most sophisticated and organized outreach effort groups in prison that prisons ever known,” says SpearIt, the scholar who studies Islam in prisons.

Malcolm X famously converted to Islam in prison. Like it was for Malcolm X, prison for many is a time of personal reflection, SpearIt says.

“For many, it's the first time they've ever been able to sit down and concentrate on something away from the chaos of the hood and the streets and all of that,” he says. “And we have to remember, in prison, it's traumatic. And there's other research that suggests that trauma, the trauma of having to go to prison, and then finally getting there and having to live that experience, these are precursors to conversion as well.”

Wendell gets to Folsom, and on the first day he’s there, he sees somebody get killed. That day, his new cell mate gave him different advice from what he heard from those county jail men.

This man said, “You have to be part of the war happening in the prison. You have to pick a side and be loyal to it.”

“He said, ‘You want to survive,’” Wendell says.

“You got to be part of this, man,” he tells Wendell. “If you don't want to be part of this, you're gonna die.”

Wendell had a choice to make. A choice that could mean the difference between life and death. Should he listen to this man inside prison and get involved with the gangs? Or take the advice from the men he met in the county jail? He was new, and he was conflicted with the mixed messages. But he knew he had to choose.

Finding the Muslims

Wendell asked where the Muslims hung out. Someone pointed him in the direction of the multi-faith chapel.

“So I went over and then went inside. And it was like, wow! This is cool. I saw the brothers all together. At one section were brothers learning the prayer. And one section, they learn Arabic. And one section, they got a whiteboard where they learned stuff. And it was like, it was cool. It was quiet. Out there was the yard. A lot of noise. Inside, it was quiet. Everybody respectful.”

One of the men introduced Wendell to the others and he felt that familiar draw that he experienced as a kid going with his brother to the Nation temple.

“You know, they glow,” he remembers. “It's a different look. Different from people in prison. You got that shine, you know?. You’re serious about what you're doing. You know, you've been educated. You’ve been transformed. Everything you're doing is different.”

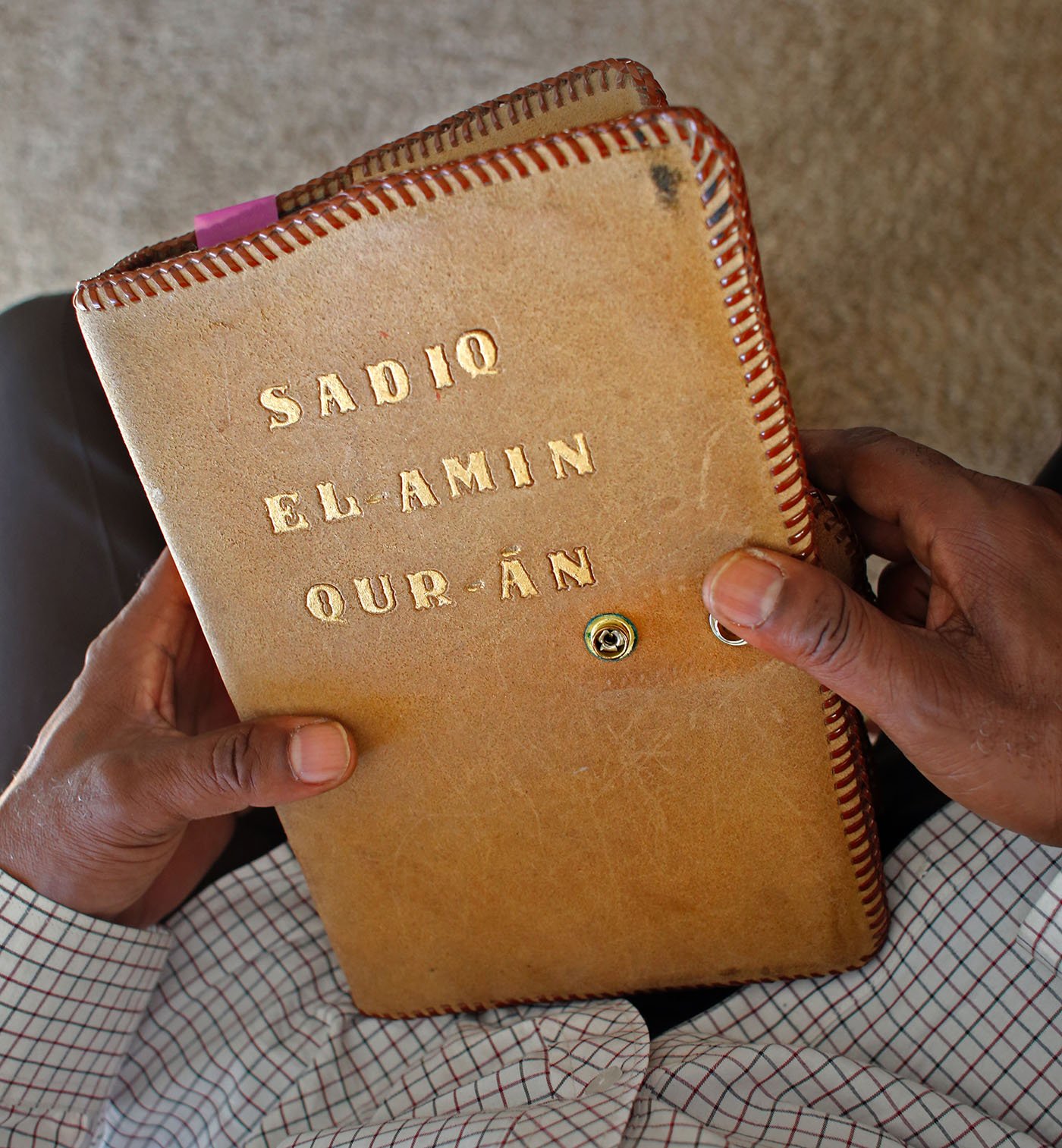

And that protection the Old G’s told him about? That first day, he stayed in the chapel as long as he could. And when it was time to leave, the Muslim men walked him back to his cell. In the morning, someone would be there to get him. He was accompanied at all times. He felt safe. He felt he was with productive people. He listened as they read from the Quran. He watched their prayers.

When Ramadan came along, he fasted with them.

He remembers how impressed he was. “I wasn’t a Muslim then. But to see how you fast. That you don't eat. You don't drink. You don't do nothing. No swearing, no cursing, no nothing.”

Wendell enjoyed hanging out with the Muslims.

Scholar SpearIt says these feelings are part of the reason why Islam is such a powerful draw for men like him in prison. This strong sense of connection, the discipline. And he says there are other reasons, too.

“People just look at their existential situation and associate that with Christianity,” SpearIt says. “This is a Christian country. These were Christians who did this to me. And I'm sitting in prison because of this system that, you know — that basically Christianity has authorized. So there is that sense that by being Muslim, you are joining something that has had a glorious past of standing up to Christianity, having glorious victories. So there is this sense that Christianity is something to get away from."

Spearit says many Black American Muslims see themselves as reverts rather than converts. Going back to the past and reclaiming powerful lost Muslim identities linked to the history of Islam in Africa and even Spain.

For Wendell, after fasting that Ramadan in 1988, he went to the Muslims and said: “I want to become Muslim. It's cool.”

“He said, ‘Why do I say it's cool?’ I say, ‘Because the way that you guys are doing things is different.’”

“You know, we got dope dealers and you got dope fiends. You got everything in prison that you got on the street. You had people doing the same things they did on the streets, they’re doing in prison.”

“I said, ‘This is cool.’”

“If I'm gonna be in prison for some time. This what I want to be. I want to be a Muslim.”

He remembers the day vividly.

“When I took my shahada,” he says, “it was like a weight was lifted off me. It was like, ‘Okay, you got this. You can do this, right?’”

“'‘You don't have to worry about nothing. You can do this.' Whatever time they give, you can do this. You know, you just keep doing what you're doing. You know, just keep reading this book. And the book is gonna give you direction outta this.’”

A difficult transition

Wendell was now Muslim, but he started going back to his old habit of dealing drugs again. He ended up in solitary confinement — the hole. He says the Islamic concept of God watching you at all times is what helped him through it.

“So when I got in the hole, I realized, hey, wait a minute. Allah is watching me, everything I do. Everything that I do, I’m being watched. So I got to make a promise to myself…I make a promise that: you can’t do this. You have to take control of your life and know that you’re not the only one in this.”

Scholar SpearIt says being in solitary can be instrumental for conversion and for commitment to the faith. Again, he points to the story of Malcolm X.

“His time in solitary is what really got him inspired,” he says. “And was the trigger for his conversion. Because when you've got nowhere else to turn and you're at rock bottom, you can only turn to God and only go upward from there.”

Wendell left the hole with a new vision for himself. He cut ties with the guys who were dealing and got back in with the Muslim guys. He started going to the Friday services. And he studied. A lot. Over the years, he slowly worked to turn his vision into reality. He spent most of his time in the chapel or in the library. He taught himself how to read and got his GED. He got a clerkship with the Muslim chaplain and earned a certificate in drug and alcohol counseling.

New religion, new life, new goals

Wendell got out on July 2, 2015. He had been in prison for nearly 3 decades. His son and the Muslim chaplain he’d known inside were there to greet him.

“My first thing that I did,” he says, “I hooked up with some people that was doing constructive things on the street, that had been in the system.”

“A lot of people would be going back into prison speaking to people in prison. I wanted to do that.”

When he got out, Wendell was 63 years old. It’s a dangerous phase of life to be returning to society. Older people are more vulnerable to being un-housed, unemployed, chronically sick and lonely.

But Wendell had a plan. He stayed with family. And he got to work.

He started a reentry support circle as part of Taleef, a Muslim collective that works with converts and formerly incarcerated people. It’s a casual monthly gettogether where folks can just talk. Even during the pandemic, they were held — on Zoom.

People open up about their lives transitioning back into society, their relationships and their challenges. Wendell’s former coworker, Alaa Suliman, used to run circles with him.

“His very open and accepting personality and energy,” she says. “He just attracts people to him to be able to just share and connect. He just has a very nonjudgmental, like all is welcome. We're in this together.”

This kind of work is critical for rehabilitation, according to scholar SpearIt. He says the Muslim version of it has a good track record.

“There's an entire discussion about Islam’s contribution to rehabilitation,” he says. “When you look at all the religions — and they've done numbers on this — Muslims have lower recidivism numbers than all the other religious groups.”

It doesn’t work for everyone though. SpearIt says sometimes people will start hanging with the Muslims out of a need for protection or to get out of the cell for extra perks.

“And so that's one of the tests to determine if someone is a sincere convert,” he says. “ Is whether they keep the faith once they leave prison. And many don't. I mean, that's just a fact. And so, you know, when we talk about converts as a whole, we have to recognize that there's a chunk of converts who weren't converts at all seriously, but were just kind of there for the ride. And once they get out or get in a better situation, they don't really stick with it.”

For Wendell, there was no question. He was committed to staying Muslim. He says he’s doing exactly what he thinks he was meant to do.

He still tells his story: “I tell people that I lived in a cesspool before going to prison. I was a dope dealer. I was one of the worst of the worst. I sold poison to everybody that wanted it. I sold it to them. The women having babies. I did that. I live with that every day. Then Allah took me from the cesspool and sent me to hell. I went into hell, literally. Literally, I've seen people get killed. I've seen grown men get raped. I've seen some stuff that people are not supposed to see.”

Wendell says he felt God was giving him a choice. Go back to the cesspool or do his work.

“And I chose to come back and do his work. I do his work today. I don't do my work, because it's not mine. I'm just a tool being worked.”

He wipes a tear. “It gives me a chill,” he says. “I get teary-eyed with this stuff. I know that Allah allowed me to come home for a reason.”

And the reason is to be of service.

“It means that I can get up every morning with a purpose.”

***

Hana Baba is the host of Becoming Muslim. She also hosts KALW's award-winning newsmagazine, Crosscurrents, and The Stoop podcast: stories from across the Black diaspora.

The Spiritual Edge is a project of KALW Public Radio. Funding for Becoming Muslim comes from the Templeton Religion Trust.